Trip Advisor: An Interview with GRAND TOUR Director Miguel Gomes

On screwball comedy, Filipino karaoke gangs, and cigarettes

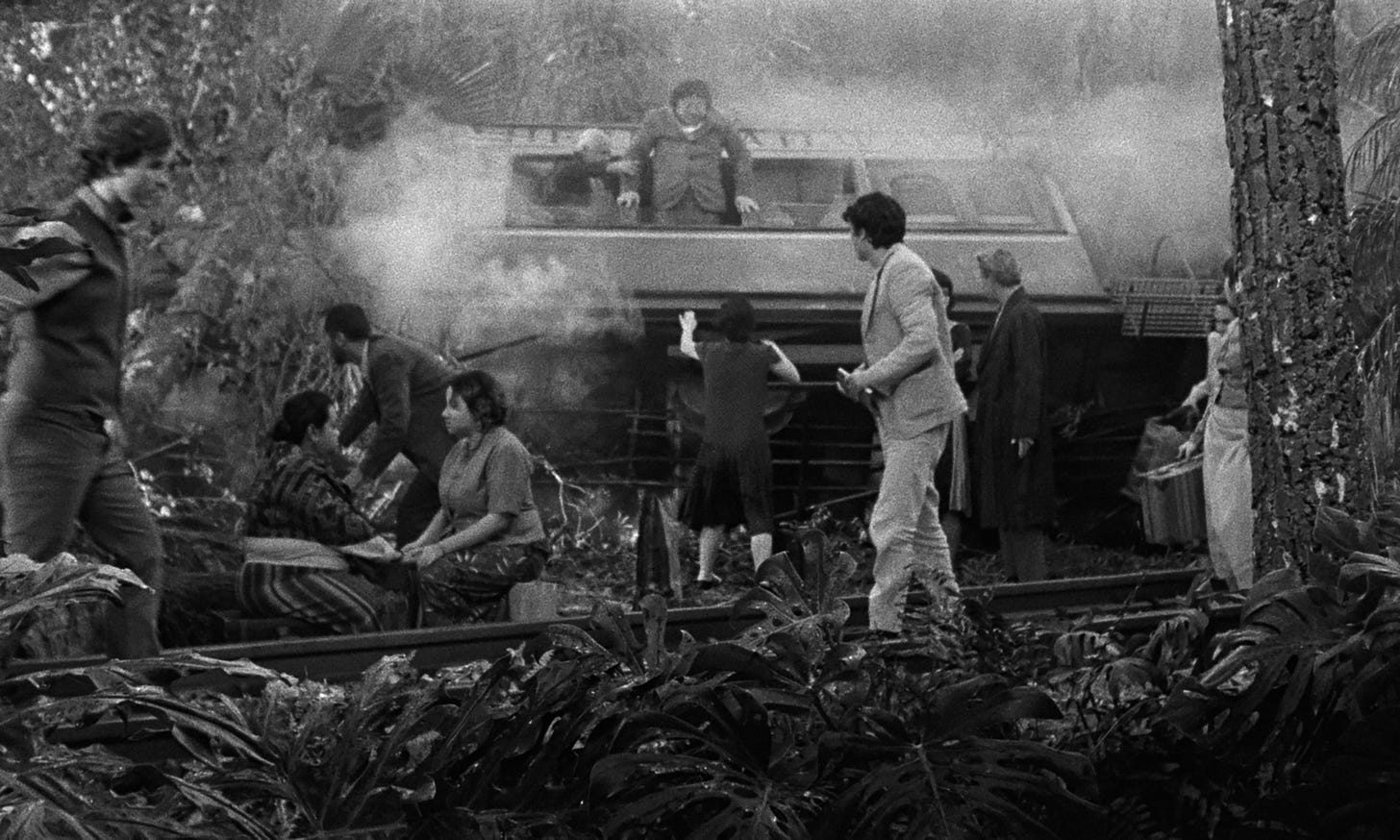

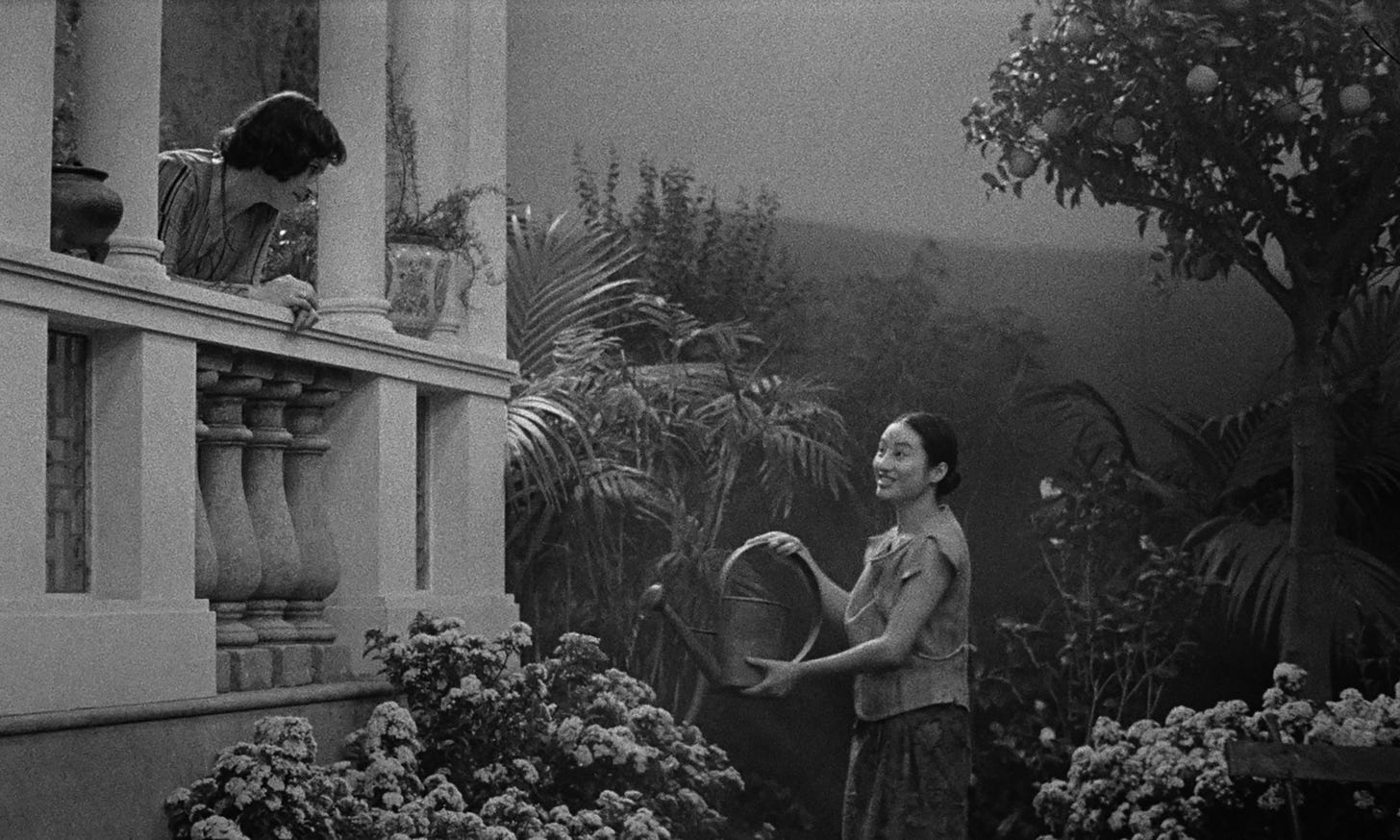

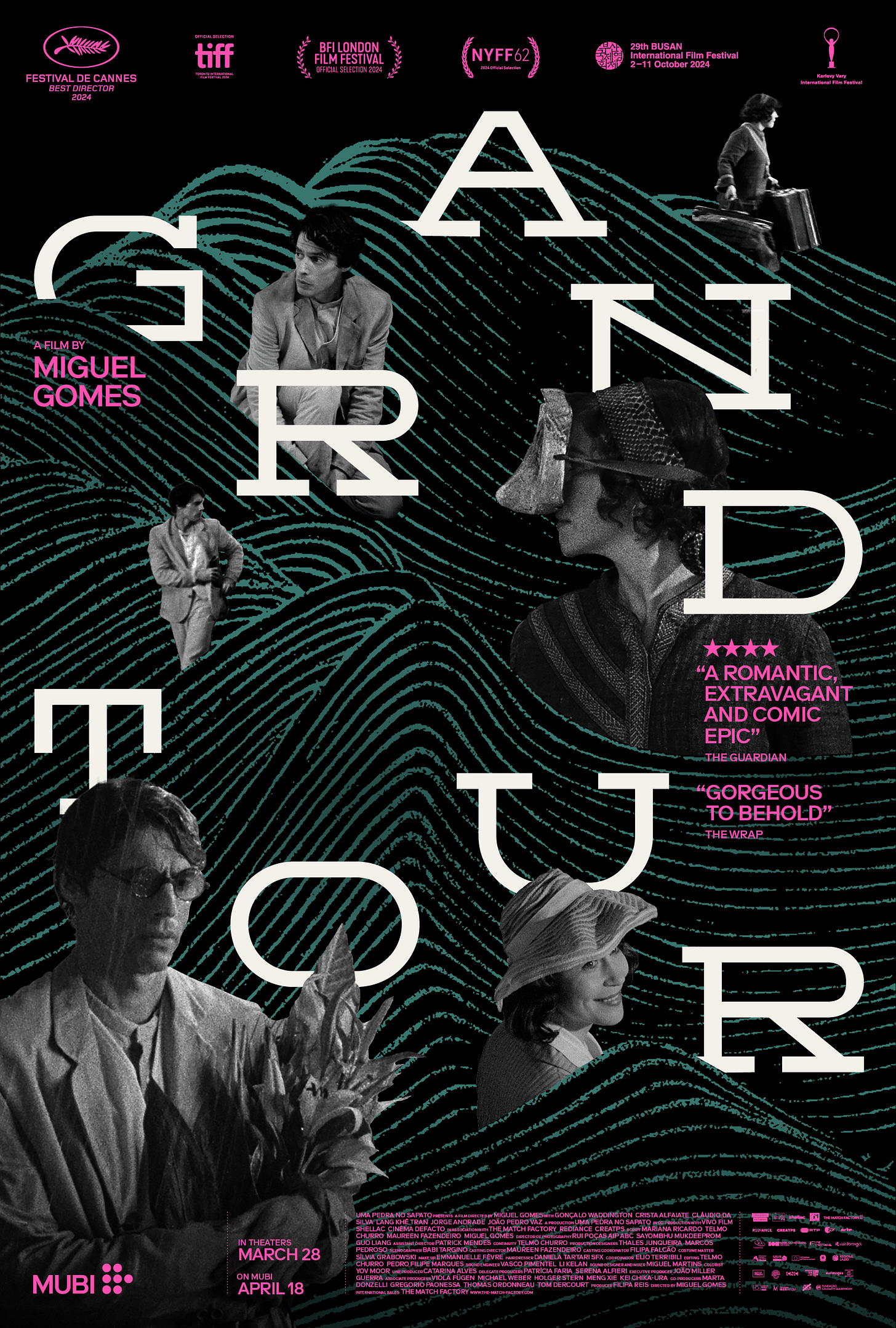

Grand Tour is a screwball comedy of doomed love, a dreamlike melange of Howard Hawks and Manoel de Oliveira. The latest sui generis concoction from Portuguese director Miguel Gomes (Tabu, Arabian Nights) opens in theaters this Friday, before its streaming premiere on MUBI April 15th. It begins with a rom-com premise - in 1918 the dandy British civil servant Edward (Gonçalo Waddington) runs out on his fiancée Molly (Crista Alfaiate) the moment she docks in Rangoon. Edward sinks into depression as he treks across Southeast Asia into China on his escape from the bonds of marriage. The indefatigable Molly decides to chase him out of pique and genuine affection. This bittersweet tale, shot in B&W in fog-bound sets, is intercut with contemporary color footage of each country, as Miguel Gomes takes his audience on their own Grand Tour that dovetails with the one of his star-crossed non-lovers. I spoke with Miguel Gomes about this bold narrative structure, Filipino karaoke gangs, and singing in the bathtub.

R. Emmet Sweeney: Did the concept of Grand Tour start with the W. Somerset Maugham short story and your marriage to co/writer and casting director Maureen Fazendeiro? How did it all come together?

Miguel Gomes: Well, it's a fact that I was about to get married. And it's also a fact that I was reading in a certain moment - not the short story, because there's also a short story - but a travelogue book that W. Somerset Maugham wrote called “The Gentleman in the Parlour” (1930), about traveling in Southeast Asia. There are three pages where he says, “I met this guy near Mandalay, a British guy, and he told me what happened just before his marriage, that he was engaged for many years.” And so he told the story of Molly and Edward.

And this guy being Edward and his wife being Molly. I said “OK, this is interesting.” So I shared these three pages with Maureen, who married me. And we laughed, both of us. And then I was thinking, “Maybe I can do this. Maybe it's interesting to do this story of these two, this strange couple, in a studio.” And at the same time, do a strange adaptation of the book itself, Somerset Maugham, which is a travelogue. So this means I cannot do a travelogue in the past.

So I have to do it today. Let's follow the same itinerary of the characters and shoot this itinerary. Let's shoot things in these countries. And then we'll try to do transitions between the story we'll write afterwards (to be shot in-studio of Molly and Edward) and the images we made, that we have filmed during our travels. So this is how the thing came up.

RES: And logistically, how did it all work with the three different cinematographers on this?

MG: One of them came by accident. We knew that from the start, as I said, that we would be in the studio with the actors and also have a travelogue made in Asia. So I've planned to have two different kinds of cinematographers that I've worked with before. So one of them is the one I worked with on Arabian Nights (2015). He's a Thai cinematographer, Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, who also works with Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Guadagnino, and other directors. So I want an Asian cinematographer to do the tour of Southeast Asia with me. And I wanted Rui Pocas, he also shot Tabu (2012), for instance. The films before Arabian Nights, I made all of them with him.

And two shooting studios in Europe. So I had these two planned from the start. And then when we were doing the journey, it started shooting in 2020. The beginning of 2020, we took a plane, I think, on the 2nd of January, to go to Myanmar. And we planned to go to China, from West to East. And then what happened is that in February 2020, the borders of China were closing because of COVID. So we could not finish the journey we had planned. We waited before getting to the studios, so we wrote the script then, we added a little bit of footage we shot in Asia. And we were trying all the time to get into China to finish this journey. And it was impossible. It was impossible because they have a policy called COVID-Zero. So no one could get in in China.

And so there was a moment when we decided, okay, let's not wait, let's just shoot remotely. From Lisbon to China, we have a 100% Chinese crew that I never met physically, only afterwards. Afterwards, I met the cinematographer Guo Liang. And I was in Lisbon directing the film, and they were there, they were doing 3,000 kilometers along the Yangtze River. And I was feeling stupid, going to an Airbnb house in Lisbon, like one kilometer from my house every night, to a room with monitors, like I was in NASA, and I was launching a spaceship, and they were in the same spaceship, and I was in the NASA control room. And that was in 2022, two years after we started the journey. And then one year later in 2023, we went to the studios in Lisbon and in Rome, and we shot the sequences with the characters, with the actors. And so the third cinematographer came because of COVID.

RES: Could you talk about what you told the actors you were looking for in their performances, especially the actress Crista Alfaiate, because her performance reminded me at times of Greta Garbo in Ninotchka (1939), or I think you've mentioned Katherine Hepburn…

MG: I said to them, these two characters, this couple, they could be in a screwball comedy. But a dysfunctional one. And I think a sadder one, because they are not together. So, Grant and Hepburn, but they are not together. I told them about, for instance, Bringing Up Baby (1938), and how the characters in these films were acting a little bit silly all the time. And how Hepburn and Grant were having fun. It was not like the idea we have now with most of the cinema, art house or mainstream, that the truth of the performance of an actor should be linked with a naturalistic approach. I mean, half of the fun in these films was that you had the feeling of them having fun. Having fun with what they could do with the characters, and just acting childish, and we could almost sense that you would say cut, and they would start to laugh. I think pleasure is something you can pass to the viewer. So I think it's always better to have fun on the set than to suffer.

RES: And I think that comes through, not just in the performances, but in the footage you're getting, the contemporary footage in these countries. I love a lot of the karaoke material, which you keep returning to, especially the performance of “My Way”, which a man really belts out, and then starts crying at his table…

MG: I would say that I like paradoxes, and I like to have two things happening at the same time. And that's when it gets interesting. If it's only one, it's less interesting. And so, for instance, while I'm shooting what we can call reality, in the world, not in the studio, but in the world, sometimes with things that are happening before me, that I'm not controlling…it attracts me to be shooting for instance, people singing or puppet shows, it's not something that I created. They can do it without the film, they can sing, they can perform puppet shows. But I think it's great when I'm shooting the fiction in the reality at the same time. So I'm naturally compelled to search for these kinds of things.

In the Philippines, the karaoke performance of “My Way” was something that we thought of doing because of a story I heard about this gang called the “My Way Gang” that existed in the Philippines. They were robbing people, but they were forcing the victims to sing “My Way” on karaoke machines and they could be freed, not robbed, if they scored 100 points on the machine for singing that song. I thought this was very strange, I didn’t believe this story. So I had to try it, to ask someone in the Philippines to sing “My Way” and the result was what you have seen. So it was just one take. So I don't know what the hell is happening between Philippine karaoke singers and “My Way”, but there’s something going on.

RES: He looked very emotional after his performance.

MG: Yeah, yeah, I think there's something going on with this song in the Philippines. I don't know the reasons. But for instance, this guy singing by the river, the Mekong River, was one of the drivers we had in Vietnam. And he was always singing, he was driving and singing. We spent some days with him and I said, “You really like this song, can you sing it for us?” He said, “Of course, I can sing it!”

And so things can be planned like the story of My Way gang. I wanted to do something with it and try to see what would happen. Or it can be because the driver is singing a song and whistling all the time. And that’s a moment we want to put in the film because in the end, the viewer doesn't have to care about these things. This is the background that we're making. But making a film is like living. In that the result can be very artificial.

I like to be artificial, not to be, you know, confounded with life itself. It's not life, it's another thing. You can put it in the film because it's happened in your life and there's someone that wants to sing a song and I have the space for it, so please sing this song. And in the end, we'll see if it ends up in the film or not.

Even in the remote shooting, where I was not able to be there, so I could not do these kinds of things, I did it. Because while we were directing the remote shooting in China, we would always cut at like 3am, 4am, for lunchtime in China, and they would go for one or two hours to eat and then they would get back to us. And in one of these moments, we were always curious about what they had eaten and a little bit envious. And then one day they said, well, we went to this restaurant and there was the owner of the restaurant, he knew that we were making a film and he went to pick up his guitar and he started to sing for us. And we said, okay, now we are going to a boat, in the Yangtze, ask him if he wants to go to the boat and sing. And you also have this moment in the film, there's a moment you're in the deck of a boat and there's this Chinese guy entering the frame and he starts to play the guitar. Knowing people and that we sense that they desire to enter the film in some way, we try to have space for them.

RES: Yeah, that’s something I love about your films, even though I know there is tons of preparation, it also seems like you're discovering things in the moment all the time. You're kept on your toes.

MG: I think you can do both, you know, you can do both because what's the problem? The problem is when you prepare too much, you have to prepare things, but you have to be able to just abandon everything you've prepared. Because, I mean, sometimes there are people that want to sing, but sometimes in a normal film, like in a mainstream film where everything is decided years before, you can have a giraffe coming onto the set and no one will notice, because everyone is trying to go with the plan. I think they are losing something.

RES: Do you personally like to sing? Do you like to do karaoke?

MG: I don't have any talent.

RES: That doesn't stop most people.

MG: Of course, like everyone, I sing in the bathtub. That’s it.

RES: Can you talk about how you work together with Maureen when you're putting together a project?

MG: It's much easier to work with Maureen than to live together. [laughs] You don't have to decide who's going to do the laundry or wash the dishes or something. So it's the good part. It's just to make a film and we both love to do it. In the case of Grand Tour, she did the writing with some others, we were four, me and Maureen and the other two people that worked with me for a long time too [Mariana Ricardo and Telmo Churro].

Maureen is also the casting director and she's quite meticulous and very obsessed. A little bit like Molly. Every extra in the film didn't come from an agency, they would be picked by Maureen and her crew. And I think it really changes everything. Because most of the time in cinema extras are a little bit like cattle. People that go from right to left or from left to right and they are like robots. And I'm more assured that with Maureen working with me, she will never neglect anyone.

RES: Before I go - last question: what's your cigarette of choice?

MG: Red everything. It can be Marlboro. It can be everything that is red.