Thieves Highway: An Interview with Director Jesse V. Johnson

Talking to the king of DTV action movies

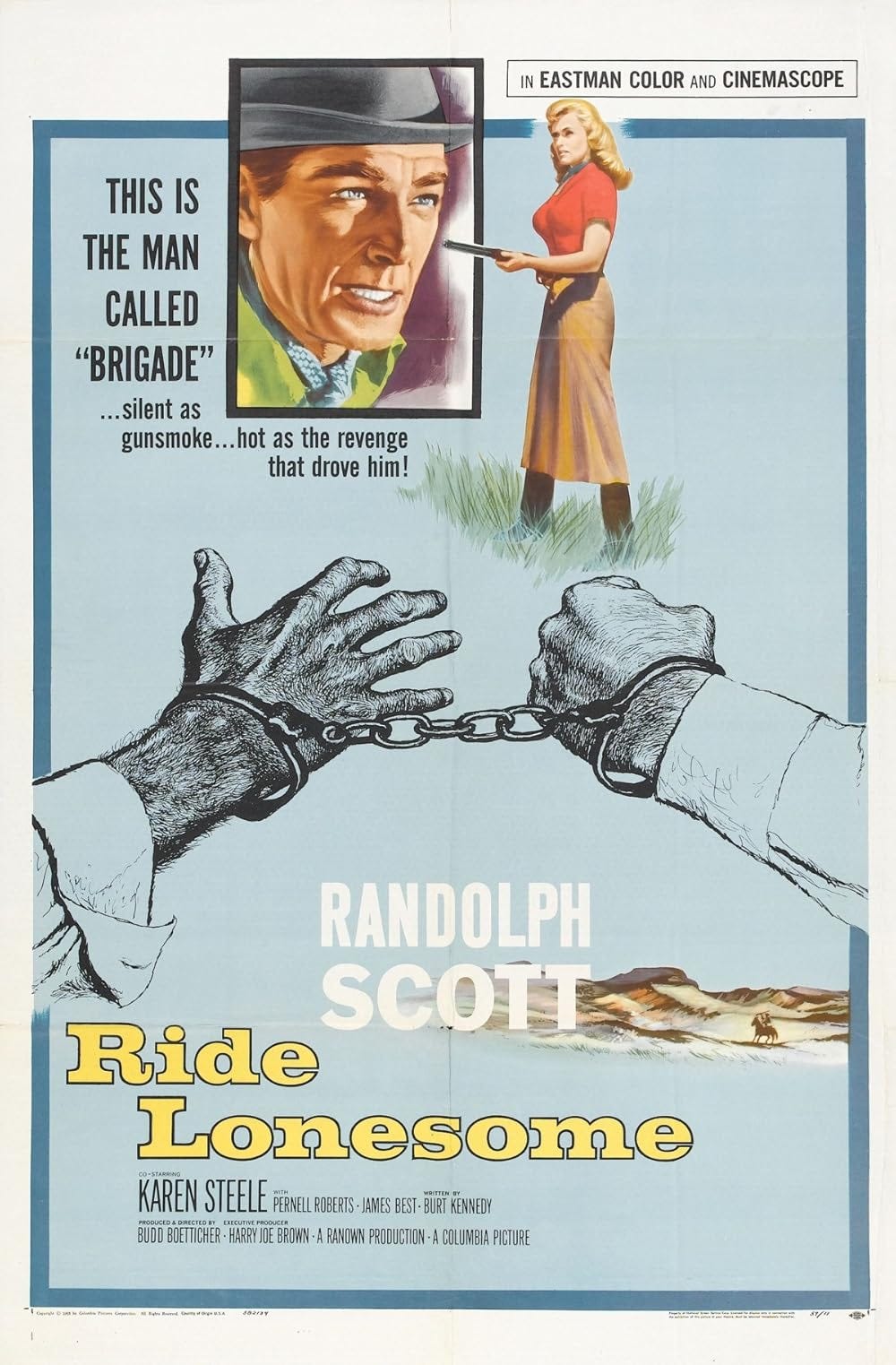

Jesse V. Johnson has been thriving in the wilds of low-budget action movies for decades now, a true independent filmmaker who has managed to work on his own terms. Thieves Highway is one of his best, a lean cattle rusting thriller that recalls Budd Boetticher’s Ride Lonesome - both were made on a condensed 12-day schedule and portray a principled man pushed to his moral limits. In a just society Johnson and star Aaron Eckhart would be fêted at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, but instead it received a very limited theatrical release (I saw it at the only theater it was playing in NYC - the Kent in Midwood, Brooklyn), and was then deposited on VOD with no fanfare. So at OLD NEW I am providing my own fanfare - I placed it on my list of the top ten films of 2025, and now Jesse V. Johnson agreed to talk with me about the genesis of the film, the challenges of independent film financing, working with Roger Corman, and Aaron Eckhart’s particular set of skills.

R. Emmet Sweeney: Thieves Highway is a gritty Western that really displays your influences. How did the project take shape and what films in the Western genre were you inspired by while making it?

Jesse V. Johnson: I had directed a film called Chief of Station in Budapest with the wonderful Aaron Eckhart, who was a last minute replacement for us. Chief of Station had originally been cast with Alec Baldwin, and I developed the script and character with him via Zoom and enjoyed it. I was looking forward to it, but there was no action in the film at all. It avoided any gun stuff for obvious reasons. And then 10 days before filming, the insurance company wasn’t going to bond him because he was about to be subpoenaed. And even though it was only a one day subpoena, they would cancel if we went with him. So we had to find someone else. And at the last minute, Aaron stepped up and he was phenomenal. I rewrote the script, put all the action back in again. We came up with sequences together. We enjoyed the same sort of movies, the same kind of physical filmmaking where the actor gets involved and does his own stuff. A similar sensibility that harkens back to a slightly older Hollywood. To a morality that he feels more strongly than me. He’s more faith-based and has a rigid moral code. Mine’s a little bit wavy, I’ve spent too long trying to get movies made. I’m trying hard to be the best version of myself I can be, but it’s a tricky business.

I was looking out for projects to do with him, and I was back in Budapest on a television series that I’d been working on with a producer. And he said, “I’m also a screenwriter”. Travis Mills is his name. And I quite like him. He’s a tough nut. Makes his own Western films. He’s an obsessive with John Ford and Howard Hawks. He runs the Tombstone Festival. He’s an absolutely independent thinker. So I read the script he gave me, which was about cattle cops. Based on conversations he’d had with a real cattle cop range detective in Arizona. So there was that taste of authenticity there that you’re looking for in a script. I get a lot of scripts written by people who’ve never been in the real world, but watched an immense amount of movies. You know, don’t throw the cat overboard or whatever it’s called, all of the books on screenwriting. They’re neat and the spelling is checked and the grammar is beautiful. But once in a while you read a script, it may not be perfectly written, but there’s something in there that smells of actual horse manure [laughs]. A description of an act, a fight sequence, a man who knows what it’s like to hit another man. I didn’t finish high school, and so when something’s too beautiful and polished, I have a strange aversion to it.

I’m looking for something that has that smell of cattle manure, the smell of diesel in the morning, the shot in Peckinpah’s Junior Bonner where he checks the oil and wipes it with his hand. This is something that someone who has checked the oil in a thousand cars has done. McQueen was a car nut. Moments like that are what stand out to me. Now they don’t assure you of having a fantastic movie. That’s my task, but you have those little pieces of spice in a script, it draws me to it. And the script that Travis gave me had 10 or 15 of those in a hundred page script. And that’s a high percentage. And against my better judgment, I liked it. I say that because whenever you get involved in something that has no money or actors attached, it’s going to be a marathon.

But also within its pages, I saw something that would appeal to Aaron Eckhart. One man against the system, morality is driving him as opposed to the need for money or the need for revenge. It’s a moral cause that he has taken on. I like someone being driven by something that’s not a base motivation. “I’ve got to kill these people, they hurt my daughter.” It just gets boring for me. It’s almost like lazy writing. I get so many John Wick rip-offs, know? I just lost my wife, I just lost my dog, I just lost my neighbor, I just lost my cousin, and I’ve got to go kill all the bad guys. And it’s boring. When I was doing martial arts movies very heavily in that world, it was all about underground fighting to save a family member. It’s a boring trope unless you do it extraordinarily imaginatively. It’s a dangerous road to go down. And Thieves Highway felt original. It felt like this was a man who had a moral purpose. I did some rewrites on it very quickly, sent it to Aaron, and he liked it enough to say, “OK, let’s take it next to the next steps”. Then I had to finance it…and that’s another story all together. It was really perilous on this one. I learned a few lessons, but we got it made and I’m very proud of it.

RES: I don’t know if you are able to get into it, the financing part of it. I know on Facebook you talked about some troubles.

JVJ: It was awful. It was truly one of the worst experiences of my life. I had to really amp myself up to figure out how to make a film in 12 days. And part of that was visiting the Lone Pine Museum to see how Budd Boetticher had made Ride Lonesome in 12 days. I went in very prepared. The crew were phenomenal. They worked their asses off. The cast was phenomenal. worked their asses off. We made the film, brought it to Los Angeles, and it gradually dawned on us that one of the financiers had dropped out and had not paid. Which is the worst situation in the world for a director. My team is excited because they get to come out and make money on this one. No one made money. Christmas was coming up. It’s just awful. So I sat on the film for seven months, not letting anyone have it. I was advised by legal counsel that pursuing a lawsuit would effectively bury the film. Delivery dates would not be met, triggering a knock-on effect that would result in multiple, ugly lawsuits, with the end result being that no one would be paid.

By contrast, releasing the film meant that many people would be paid, and others would at least secure a deal. It was a no-brainer. Many of these individuals have worked with me for over 20 years. So I released the picture edit. Post-production—comprising 10 to 15 people and vendors—was paid, followed by the two major guilds, SAG and the DGA. The Producers, in turn, committed to working through the remaining crew and paying them out. That’s where things stand now.

RES: So it’s still an ongoing issue.

JVJ: I believe there are still people on it that are waiting to be offered a deal. I’m not privy to it. The best I can do is get another picture going and get everyone back to work and paid off in kind. I wasn’t a producer on the picture. I wasn’t involved in financing in any respect other than taking the script to them and getting the deal to get it made. Prior to ours, there was another movie financed by these guys…Starring Tommy Lee Jones and James Franco, which had similar issues. A lot of films in that year had similar deals with financing falling through. People were pulling out of pictures. Guy Ritchie’s picture had a problem. At least three other films by independent directors that are peers of mine that I know I talked to had similar situations happen. I don’t know if it was a post-COVID, post-writer’s strike issue or it’s just the nature of independent financing.

It’s difficult. You go to a studio, you’re financed. But you go to multiple independent financiers, everything can be going great. And then one is bullshitted and he drops out and then that causes a knock on effect. Another one gets cold feet and another one does as well. And suddenly you’re left high and dry and you might be on location. I had it happen to a film where I was in Bilbao, Spain for nine weeks. Prepping it, location scouting, my crew from the US comes out. And suddenly, one morning, we’re told by the EP, “I’m sorry, guys, there’s nothing. The financing hasn’t come through”. The distribution deal was based upon that financier coming through. We’re high and dry. You’re trying to figure out how to get home. It was heartbreaking. You try to learn what to look for, but sometimes it doesn’t work out. Thankfully, Thieves is at least partially handled, with a lot of the major players paid, I would say 75% handled on that front, but quite a few left unpaid, which is still awful. The film had to be delivered though, or no one, absolutely no one would have been paid, period, end of story. People need to know how perilous it is to make these kinds of movies. But the film is a testament to the hard work that everyone put in.

RES: You’re trying to be a man of principle just like Aaron Eckhart’s character in the movie.

JVJ: It’s a little more complex than chasing a cattle rustler. Sometimes you really wish it was that simple, that it was just a case of chasing down those guys and shooting them or hanging them, taking them to justice.

You have two or three livestock detectives to cover this enormous square mileage, thousands and thousands of square miles. There’s no reasonable way that these guys look after them on their own. They’re traveling around at night against guys who are the lowest of the low, the cattle rustlers, they’re meth heads, they’re guys that have a basic understanding of cattle, desperate to pay the bills. And they’re out there armed. Back up the truck, they cut the wire and they shake a bucket with feed in it and the cows run towards the empty trailer. Then they can take it to a no-brand state and sell it. And the fact that this can happen so easily and that these farms can be destroyed financially when they wake up the next morning, they have nothing, they’ll have to sell the farm. There’s no way of recovering because they don’t have that kind of money in the bank to replenish.

I don’t quite understand how in the 21st century, it’s a problem, but it is. You watch interviews with these farmers, they’ve lost everything. And so with that in mind, Aaron and I wanted to paint a picture of that.

RES: It’s very affecting because these agents, they seem to be forgotten, nobody knows about the work they’re doing and how dangerous it is. In the film they mention how little money they make. They’re clearly not doing it because they’re getting rich and famous. They’re doing it because they believe in the work.

JVJ: Absolutely yes, the pay is awful. The fascinating thing about the interviews with these cattle cops is how privileged they feel to be doing what they’re doing, to be working with animals, to be doing this with a sense of honor and integrity. I think they truly feel that they’re doing the right thing. And that I found really refreshing as well. There’s no cynicism there. These guys and women look and sound like they’ve stepped out of the 19th century.

RES: Aaron’s performance - he definitely has the taciturn, upright performance of a Randolph Scott. Did you tell him to watch Ride Lonesome?

JVJ: I told him to watch it. I sent him all of the stuff. The amazing thing was when I went to the museum in Lone Pine, they had a self-published journal on the making of Ride Lonesome. So I sent a lot of this material to Aaron. I’m not sure how much he looked at it. One is always wary as a director of telling an actor to look at another actor’s work, even if it’s the guy that hasn’t worked since the 1950s. But I did send him clips from Ride Lonesome and said how unique it is. And he responded very positively to all of that. Aaron owns his own ranch which he sublets to cattle breeders, so he’s very aware of that lifestyle in Montana. He works outside, it takes a day for him to call me back because he’s out fixing fences.

RES: He can bring that authenticity to the role.

JVJ: Exactly. When I work with him on a script, I fly to Montana and I meet him in Bozeman and we go through the script. I’m very aware of him having that rugged real world element that he can add to it that feels authentic. It looks real because he’s watched it and seen it and lived it. Yes, it’s fakery. Yes, it’s acting. But also, it’s based on real knowledge of how those kinds of people react to a problem. Talk about a wild coyote on the property. It’s not a case of trying to shoo it off. They take out a .45 and pop it, because they know the consequences of what that coyote is going to do if it keeps returning to the farm. It’s not that they don’t love animals. They work with them every day and ensure their safety and well-being. But when it comes to the coyote, it takes a .45 to the skull. It’s not bloodthirstiness. It’s not bloodlust. It’s not a lack of empathy. It’s actually the opposite to that. And this is something that people need to understand. We think one way because we’re transposing our city way of thinking onto things. It’s good to know that way of thinking exists. I find it very valuable. I would never kill a coyote. I wouldn’t kill animals. That’s not my thing. But I like to understand the person that understands that world. I’m not a violent person in reality. I am fascinated by violent characters, by what drives them and what constitutes their instincts.

RES: How did you approach shooting the landscapes in this one? Did you want it to be like a Monument Valley?

JVJ: Well, I would have loved to have done it there. Two weeks before filming, the location was set. We were told it’s Columbus, Georgia. I took a lot of time scouting every single day from six in the morning till sundown. We found these huge open spaces in Columbus which were enormous. We had shots in this movie panning from right to left that involved 10 miles of landscape that had to be cleared. So we had to park the trailers almost 45 minutes away from where we were filming, which introduced all of these challenges that you don’t think of when you’re making a movie. This is not what you should be doing on a low budget film at all. Thankfully the crew were wonderful. The stuntmen were completely gung ho. And we got these shots that were much bigger than our tiny little movie. And that beautiful, orange clay earth that they have in Columbus, I adore it.

When I went into color correction on this one, phenomenal guys I’ve worked with before - they did Boudica for me - and I gave them a mandate on this, which was: don’t try and tweak it to make it look like Mars or take the green and try and make it look like anywhere else. Reach as deep into what is actually there in Columbus as possible. Because a lot of times, everyone gets scared of the amount of greens, it ends up looking overpowering. But in this case they did a great job, they really locked into the organic colors. And I was very happy with the photography that Jonathan Hall did on this one. He has been shooting for me going back to Charlie Valentine (2009) and through all of the Scott Adkins movies. And we’ve created a shorthand between us that works very well, which is not wanting to make the audience aware of the cameraman. Trying to be as invisible as possible and letting the actors, the action, the color tell the story. Not having the ego to whoop in with these close shots or these shots that are carrying through someone’s head and into their earwax and then coming out the other side of the car. That’s where you’re showing off and you’re saying, “Hey, guys, look at me. I’m a new director. I want to be noticed”. Trying to avoid that stuff like the plague and go in the other direction where you are invisible. It’s difficult because you see points where you can put something in there that’s really flashy, handheld, that’s going to make you look cool. And you say, no, that’s the ego. That’s our mandate. And we try to stick to that as much as possible.

RES: It’s a very classical Hollywood approach, the invisible editing. And it’s very effective in this.

JVJ: I hope so. You wonder sometimes. Because you see a film that gets all of these plaudits and everyone’s going wild about it. This story is really boring, and these shots are stolen from Guy Ritchie circa 1994.

RES: Any films in particular you’re referring to?

JVJ: No, I’m not going to say anything about that. That’s not cool. But my point is it sometimes makes you second guess your approach to filmmaking. But then I feel... It’s a long game and I want to be known for a body of work. You’re trying to aspire to a poetry, a grace of filmmaking as opposed to a vulgar display of knowledge of technique.

RES: A lot of these long takes, it’s like a parlor trick because they’re hiding a lot of cuts

JVJ: And you’re copying bigger versions of what Sam Hargrave did in Extraction, who I worked with as a stuntman. And his pictures, the ones with Hemsworth, are fabulous. He’s mastered it. And if you try to copy that with a tenth of the money, you’re a plagiarist. I’m very careful to avoid the John Wick ripoffs, the Extraction ripoffs, and we get so many coming through. You’ll never have the time they had or the freshness, it will be another year before yours comes out.

And as I say, the goal is a body of work that talks to not only storytelling, but a philosophy. Not the guy who is driven by dark motivations who just wants money, just wants revenge. Although that element can be touched upon, you want there to be a state of grace that your lead character has to go to. As a student of filmmaking, those pictures seem to be the ones that resonate, that last through time. The Searchers, it was awful motivation for the first three quarters of the movie, but he had this incredible passage of learning and growing. John Wayne was able to grow into something else by the final act and you have that incredible moment where he picks her up instead of killing her. If that’s what we’re aspiring to, I think that’s a good thing. That’s proper storytelling.

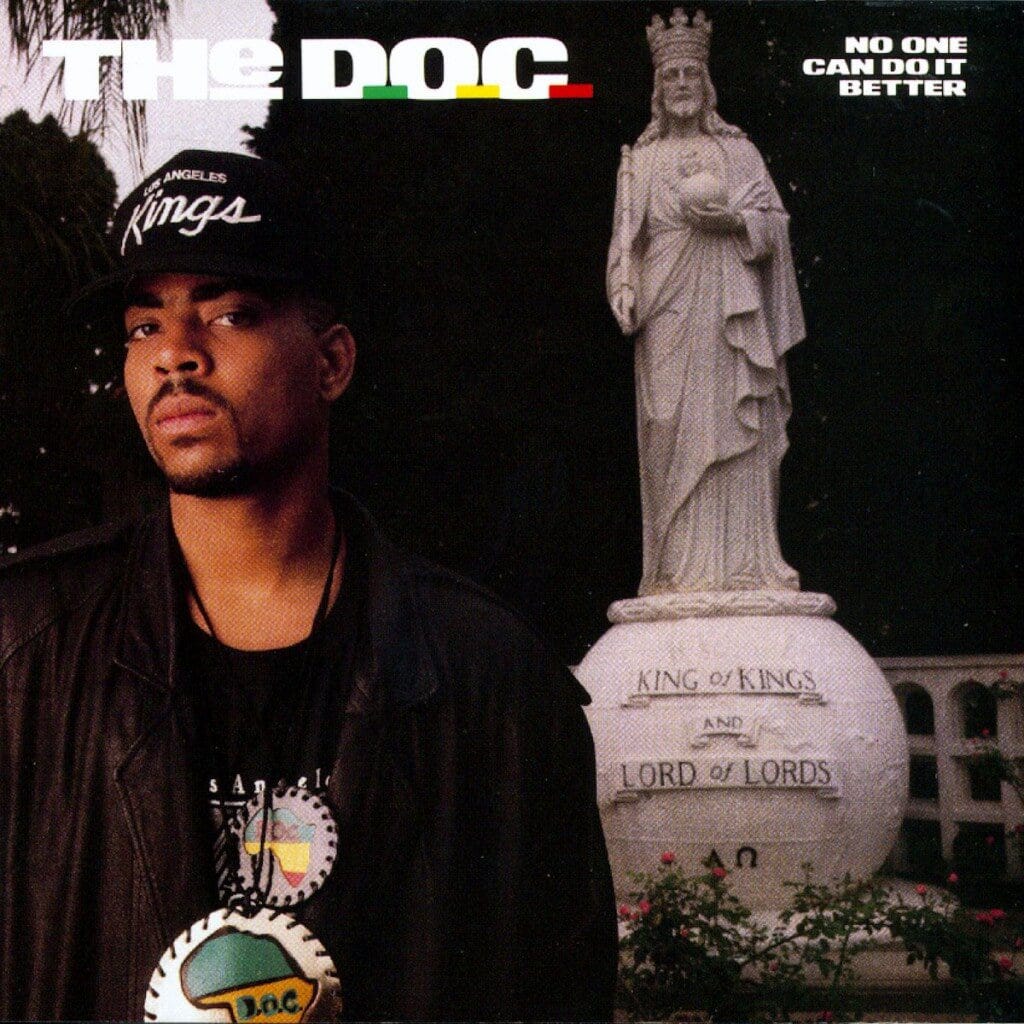

RES: One thing that really I thought was moving in Thieves Highway, these are guys, even though they’re working for the government, they’re on the edges of society. And Eckhart’s only help comes from a Black survivalist (played by rapper The D.O.C) also living on the outer fringes of society.

JVJ: He’s so bloody good. None of us knew what he was going to be like. He was just wonderful, absolutely intimate and fresh. He said, “This is the first time I’ve ever had this kind of dialogue. It’s great.” And I’m so pleased with it. And there’s an innocence to him. He rapped on NWA’s Straight Outta Compton. This is a guy who’s an actual legend in hip hop and just the most incredible human being and an incredible actor. Aaron loved working with him. And I think he really brings that, not cynical but playing cynical feel to it.

RES: Yeah, because they’re from totally different walks of life, but they’ve both been marginalized in different ways, and they connect on that level.

JVJ: I wanted to show a little bit of the anger and the frustration of what was going on, driven right to the very limit. And they put the rustler (Devon Sawa) in a noose. Eckhart has that anger in him, as we all would in that situation. But right up to the 11th hour, right up to the 11th minute of the 11th hour, we’re not sure whether he’s going to go over the edge to the dark side. If you take a man and you push him to the very limits, if he’s a real man, he will pull back. He will have that power, that self-discipline at the last minute to say, “No, I’m not going to become as bad as you guys, but damn it, I want to.” There’s a version of the film where he hung him. The police turn up and they have to unhitch him. You become so close to these characters that you’re not quite sure what was morally correct or not. Now it seems absolutely right to let him off, but for a little while there I wanted to hang him.

RES: Was that in the original script or did you change it?

JVJ: Yeah, the original script was definitely not hanging. Travis was far more black and white in terms of how he saw it. I got so into the character, I thought that he should hang him. I was like, “I’m going to hang this bastard. He’s killed all these people.”

RES: It gets feral in that gas station. Brutal.

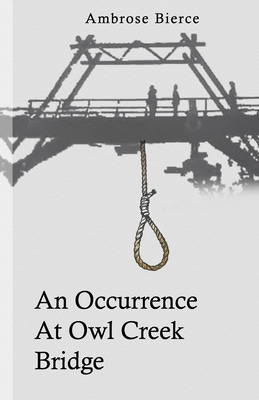

JVJ: Exactly. Maybe that would have gotten the film more notice. God knows they didn’t do any P&A on this film at all. Just released it. But where we are is the right way to deal with it all and his character and I think it’s the right statement to make. At one point I had this Occurrence At Owl Creek Bridge sort of thing where he imagines hanging him but he hadn’t. He actually let him off. It didn’t quite work. It also wasn’t the correct tone for the rest of the film. Now you’re jumping into this abstract world of 19th century poetry.

RES: I was definitely feeling how long you drew it out. I was like, “Is he really going through with this?” Because that would have been really, really dark.

JVJ: Ambrose Bierce is the name of the writer who wrote An Occurrence At Owl Creek Bridge. He was a huge influence on me when I was first wanting to become a writer and playing around with this and his writing is extraordinary. He mainly wrote stories set during the Civil War where he was a participant. And it’s interesting to put those elements in. He wrote an interesting book called The Devil’s Dictionary. He’s one of those authors like the writer of Treasure of the Sierra Madre where no one quite knows what happened to him. So if you look at a chronicle or any sort of online information on it, it says born 1812 and died question mark. It would be wonderful to have a question mark at the end of the day. Not sure if they actually died or not.

RES: He might still be alive.

JVJ: With a long beard and a jar of moonshine. B. Traven, the novelist who wrote Treasure of the Sierra Madre, also has a question mark by his name. John Huston apparently thought he met him, wasn’t 100% sure, but a guy came out to the set of Sierra Madre and said he was a business manager for B. Traven. But by the end of the meeting, Huston was suspicious that it actually was B. Traven. But he also kept very secret. No one knows when he died. It’s fascinating. It has nothing to do with Thieves Highway though, except for the ending at one point that harkened back to these guys.

RES: I read that one of the producers was insisting that Aaron take his cowboy hat off. Is that true?

JVJ: It was all of them [laughs]. And it was driven by the foreign distribution of the film. Apparently cowboy hats are the kiss of death in foreign markets, you know, which is these markets like AFM, Berlinale, and wherever. Not to be confused with the festivals, but the actual markets where these kinds of films are sold. And a film like this, in this day and age, has its major market in the foreign sales arena, not in the domestic market, which over the last few years, has come apart a little bit in value. So when you get information and missives from the foreign sales guys, you listen to them. And it’s not about being a rebel or being Sam Peckinpah tough and going against your producers, you want to make their job as easy as possible. I love working with them because I like longevity. I want to be able to come back and make more movies.

We did get a lot of emails about reducing the wearing of cowboy hats in this movie, which is sort of upsetting and distressing and annoying. So I had to work with that. The hat blows off as he’s running to get those rustlers. I made sure a lot of the action perpetrated without the hat on. Devon Sawa’s character doesn’t wear a hat. And that was the compromise. In reality, all of these guys in Oklahoma would very likely be wearing some form of sun protection. Whether it was a baseball cap or a cowboy hat. I love cowboy hats. I love that people like Ford and Hawks and Peckinpah and Boetticher would choose specific hats. In Sergio Leone’s case with the bullet holes conveying the fate of a character. Gordon Dawson was wardrobe supervisor on the Wild Bunch and was very particular about wardrobe and the amount of backstory that was given to the character. It was quite heartbreaking not to get to use them to the full degree.

We had a wonderful wardrobe designer on Thieves Highway called Donnie Hollywood McFinely who I had worked with 25 years ago. He was a PA in the wardrobe department on Shawshank Redemption. I was a PA from Shawshank Redemption. So we met each other back then and got to work together in our goal positions on Thieves Highway. We were heartbroken not to be able to use cowboy hats to their fullest degree on this one. But that’s life, and it’s a compromise. I’m secretly very happy that the cowboy hat made its way into the poster for not only the domestic, but also the artwork for the foreign sales. We did end up using that in the end anyway.

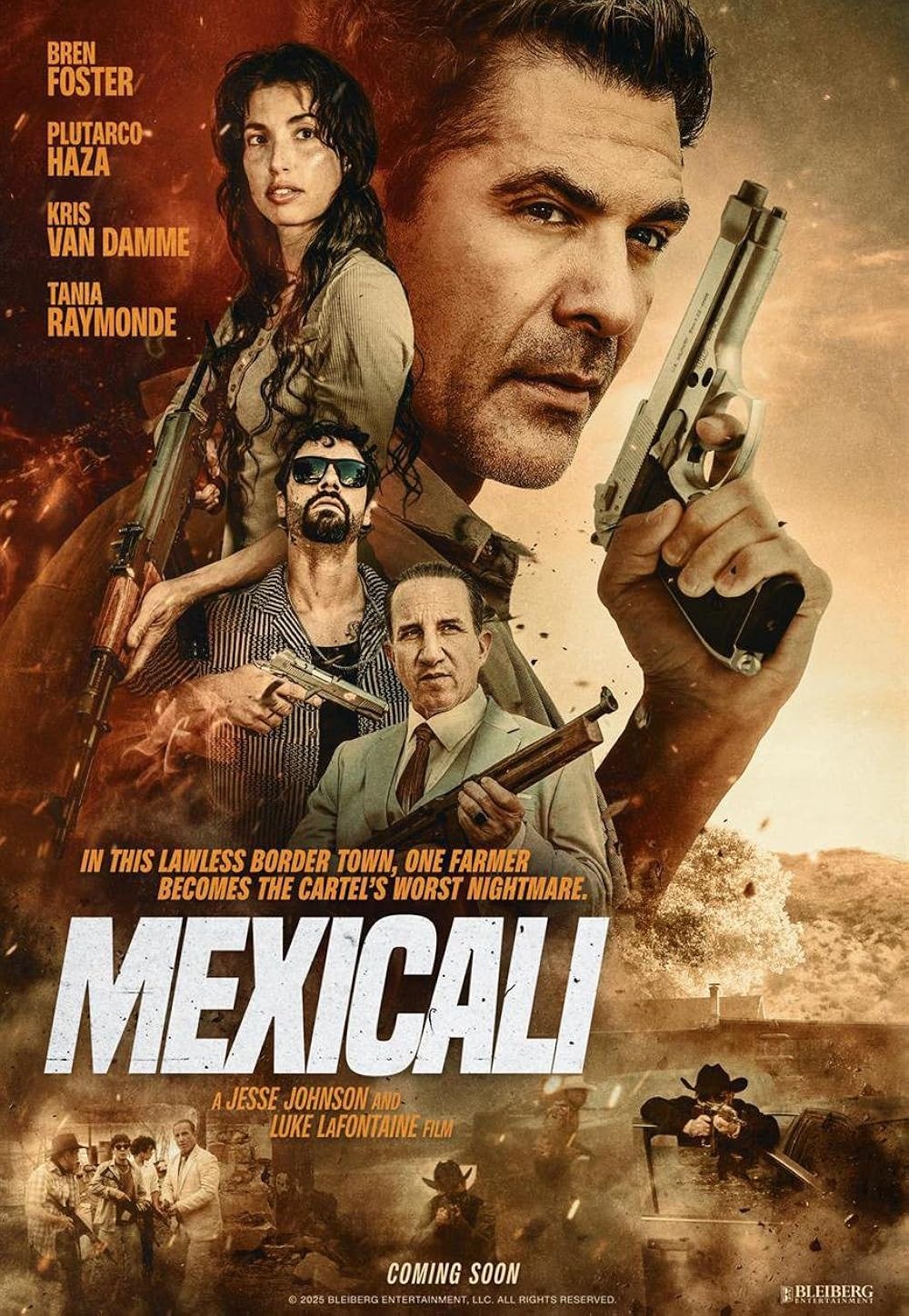

RES: I’m really looking forward to Mexicali, an action film that’s coming out this year that you wrote the screenplay for.

JVJ: I did. Luke Lafontaine has been a wonderful collaborator and a close friend for 30 plus years. We started out together on our first job, I think it was a Samurai Cop or something like that. We were both stuntmen and heavy into martial arts. He’s an extraordinary martial artist and swordsman. And we’ve been friends ever since. And he has directed second units for me. He has coordinated. He has played many parts for me over the years where I put him in and dragged him behind cars and shot him and blew him up and beat the living hell out of him. On Beowulf, which I co-stunt coordinated for Zemeckis, we broke his leg in front of the crew. Got his leg caught in the mats and it snapped. The PA vomited. It was a really violent moment.

So we have a close history, colorful, traveling all around the world. He was in Spain when the film fell apart. He was in England on Avengement and Boudica with me, up to his knees in mud. So I felt I owed him the chance to direct a first unit. And I could not afford to direct a film of that size anymore. Unfortunately, my bills have become so ridiculously over the top that I have to go do bigger movies. But I thought it might be an experiment to try producing as I hadn’t done that before. I had a script that a smaller company, Bleiberg Entertainment, wanted to finance. I had a wonderful relationship with Bren Foster, who had attached himself to the script many years ago. And I thought this might be a really fun experiment to see how it went and to pay Luke back for all of the blood, sweat and tears and bones broken that he’s given to me over the years. And so we endeavored to do that. It was a very short schedule, but he killed it. I think the film is beautiful. It has a wonderful story between the leader and antagonist that Luke brought to life with the actors. He’s been an actor for a long time, so he really knows how to talk to them and they enjoyed it and the fights are good in it. I’m not a big fan of doing the martial arts stuff anymore. I find it a little bit restricting, but he loves it, and Foster is absolutely world-class, I mean just a force of nature. He’s a walking visual effect when it comes to what he can do. Awe-inspiring. I’m very proud of what we pulled off and I don’t know if I’m going to produce again without directing. It takes a lot of energy. It took as much energy out of my system as directing. I do need to be careful because I’m not a spring chicken anymore. I want to focus on making films as a director.

RES: I loved the action scenes in Bren Foster’s Life After Fighting, so I’m curious to see him in a different context.

JVJ: He takes it really seriously. He’s primarily an actor. The martial arts was something that he did as a side thing. He is a trained actor and has taught acting, very serious and traditional. He works very well with Tania Raymonde, who we had playing opposite him. She’s wonderful and gives a really beautiful performance. It’s something unique in a genre where everything seems to be based around the fight scenes and you rush through the character development to get to the next fight scene, rush through the romance to get to the next fight scene. And this has its own pacing and it’s beautiful and it works really well. So I truly hope people respond to it. You can never really tell what they’re going to like. In my film history of 25 pictures or so there’s ones that I thought would be a sure thing. I thought Boudica was going to be a world changer for me. I put so much of my soul into that.

RES: I love that film.

JVJ: For some reason it didn’t trigger the enthusiasm in audiences I thought it would. And then pictures like Avengement, which I thought was going to be another B movie, but it became this thing that has probably caused financing to more of my movies than any other, and has intrinsically shifted my career from being a hobbyist director to being a professional director. It went from having to do stunts to pay the bills and maybe doing a little bit of directing on the side to not doing stunts anymore and being able to pay all of my bills as a director, which is a gift from heaven. Avengement was one that none of us thought was going to grow the way it did.

The one that I get the most emails about is between Debt Collectors and…One Ranger is the other one. I thought that was going to be a disaster. It was 10 days in the UK, three days in California, and then we had to go down for two and a half months, and then I flew back to the UK for one day with John Malkovich, and you’re like, how could this ever be watchable? How could it even be a finished movie? The schedule is not even what Roger Corman would have made. And by the way, I worked for Roger Corman for a year. He would not have attempted to do something as stupid and as foolhardy as this. Between Avengement and One Ranger, more emails and texts about that one. When there’s going to be a second one, it’s just strange what resonates with an audience over time.

RES: Could you talk about your time with Roger Corman?

JVJ: With Roger Corman, I did four films. It was right after Carnosaur 2. I worked in the art department on Caroline at Midnight, Bloodfist 3 or 4 I did set design, set decorating, PA-ing. You’d basically be there and they’d figure out where to fit you in. I was living in a single apartment in South Central, LA and had a motorcycle. I was doing anything that I could to keep my head above water. And I think for a year and a half, 600 South Main Street, I slept there at some points in between gigs. Working there was a joyous experience. But it’s a time in your life when the money doesn’t matter as much as the fact that you’re in motion, you’re moving and you’re learning and you’re talking to people. At the end of the week, there would be a check of some sort. It barely covered anything, but I had barely anything to cover so it was okay. I don’t think I would want to return to it as an adult [laughs].

They had a jacket that said “Roger Corman’s School of Film” on the back of them and it was very much thought of as a process. All of the famous directors had gone through there and there were no real careers being made there anymore. A factory making foreign sales-based movies as quickly as possible. but it was cool. That is how you learn the craft, by working, by working, by working. And I don’t regret it at all. But yes, I don’t think he would have entered One Ranger under the circumstances.

RES: Corman wouldn’t have approved of that one.

JVJ: Thomas Jane was so wonderful, he rolled with the punches. He’d say, “So how are we doing this one?” I’d explain it and he’d just shake his head. It’s like, “OK, let’s give it a shot”. It was the first big star that I’d worked with. The other guys were coming out of the same feisty world of low budget. Thomas Jane had worked on big, big movies and knew how it should be. You make these films under these conditions and you’re like, how could that work?

RES: Is there anything you’re working on now that’s coming up that you’re able to talk about?

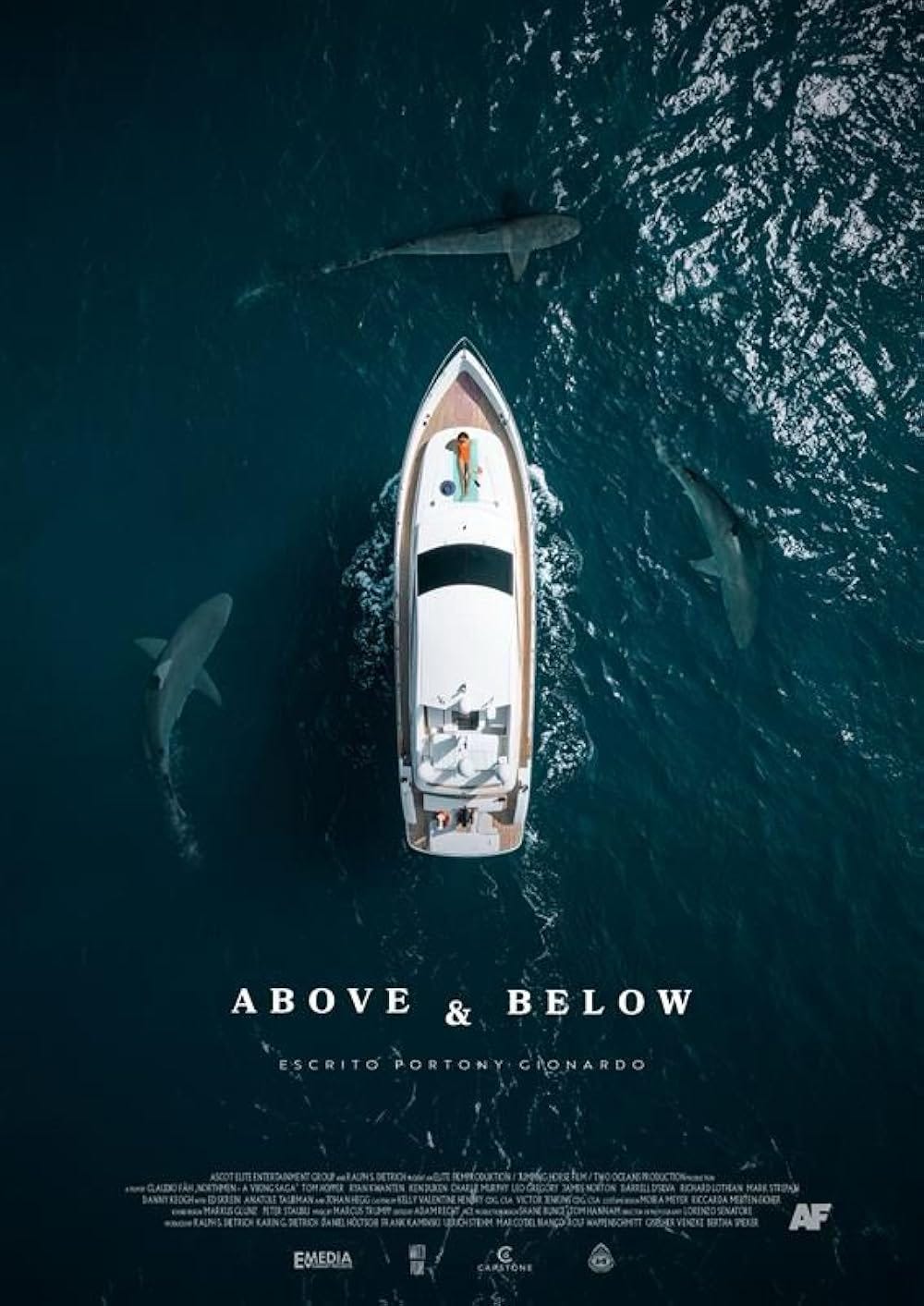

JVJ: In post on the Antonio Banderas shark movie Above and Below, which I’m very excited about. It’s coming together really nicely. There are sharks in it, but it’s a thriller. And that was a joy working with him. I got to bring Louis Mandylor out. He’s someone I love working with. He’s a great character and really held his own along with Timothy V. Murphy. Really held their own opposite Antonio. It was a joy for me because I’ve worked with Tim for 25 years, with Louis for all the way back to the Debt Collectors. And I’ve watched them grow as actors. Tim did Hell Hath No Fury with me, along with Louis, you know, during COVID. And we had a lot of critical success with that one. So to be able to bring them to Spain and put them into an Antonio movie and watch them in a scene, going nose to nose with him, yelling and screaming and pushing each other around and really getting into acting. It was exciting because I’m like, “These are my guys, these are my family.” So that was an exciting sort of experience and the film has come out really well. It’s a thing I’ve made in the past, which is an exciting thing to be a part of.

And then a third picture with Aaron. I’m not going to talk about the script because I’m Irish and slightly nervous about jinxing myself. But we are utilizing some of his skills - it’s a skill set like no other. And the dude is a competitive driver, he’s a ranking martial artist. And he lives the life, man. Gets up at four in the morning, he trains and trains and does all disciplines and goes to bed very early, like 6-7 PM, careful when I call him. But you unleash him, watch him in an action movie, and it’s like, this is unbelievable. Why has anyone not done one before? So I’m hoping to utilize all of these skills in the film. We touched on it a little bit with Chief of Station, with the driving, but I didn’t know the extent to which he was so adept at this stuff. So hopefully we’re addressing that. For example, I went shooting at Taran Tactical with Taran Butler and the top guy that’s been through there is Aaron Eckhart. No one knows it, but he’s just unbelievable with a handgun and the speed shooting. Trying to utilize those skills with this next one.

Wonderful interview. I always love when you get to talk with Johnson. He is such a straight shooter.

Heroic work.