Opening The Cloud Door: An Interview with Omar Ahmed and Ranjit S. Ruprai

Launching a Home Video Label for South Asian cinema

UK film programmers Omar Ahmed and Ranjit S. Ruprai have filled their shelves with home video releases from all over the world. There is a gap in their collections, however, as South Asian films are continually passed over for Western distribution. They cling to their 1990s era DVDs as entire generations of filmmakers have not been represented on Blu-ray and 4KUHD, relegated instead to hide on streaming sites’ back pages. These films are thus removed from the cultural conversation.

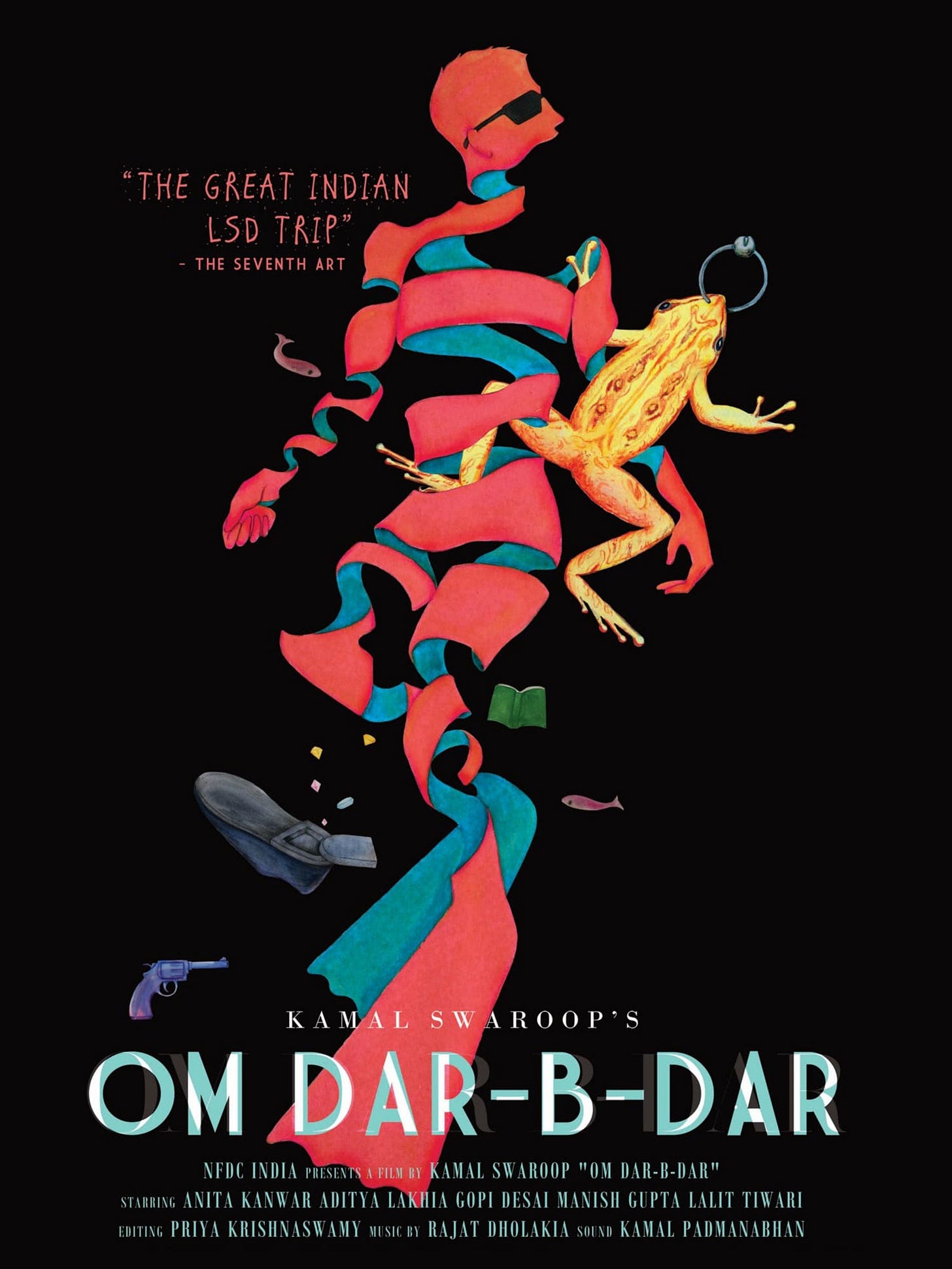

Whether this oversight is due to overly pessimistic sales projections or the complexity of licensing issues, The Cloud Door is their way to fill that empty space on the shelf. Named after one of their favorite films - an erotic-poetic short by Mani Kaul, they are launching a boutique label dedicated to deluxe treatments of South Asian classics, giving them the respect deserving of what should be canonical works. Ahmed and Ruprai have launched a Kickstarter campaign to get The Cloud Door off the ground - and to fund their first release: Kamal Swaroop’s occasionally banned and highly influential 1988 cult classic Om Dar-B-Dar. If you consider yourself a cinephile - there is no more valuable way to spend your money - the campaign runs through July 31st. I spoke with Ahmed and Ruprai about the genesis of the label, the importance of home video to immigrant communities, and the trippy pleasures of Om Dar-B-Dar.

R. Emmet Sweeney: I was really thrilled to see that you were starting this label because Indian cinema, unless it's a new release, is hard to track down in the US. How did the idea for The Cloud Door start?

Omar Ahmed: It’s been bubbling away in the background for over a decade, I'd say. We had discussions about why there isn’t a label putting out all these incredible South Asian films. In particular Indian films with the kind of rich history it has and the classic films that are out there and not available to watch in the way in which films from Europe, from America, are, and that are given that boutique treatment. So it was always a bit of a mystery. And I think as film programmers and curators, we understood and realized what we're up against because of the difficulties with licensing films. That arguably has changed over the last couple of years, but it's still a very difficult and tricky landscape to navigate.

We're both collectors of Blu-rays, DVDs, vinyl, and VHS, going back to the 1980s. And really The Cloud Door came out of that, that it should be something like this. I think other labels have dabbled in this, but have not really committed themselves to go full on. So yeah, it was to map the real interest and passion, and open a door really for film collectors and audiences to get these films out. Maybe Ranjit, you could perhaps follow up on that.

Ranjit S. Ruprai: Yeah, this is something that Omar and I have been discussing for a while. Home video has traditionally been quite a big part of immigrant communities not just in the UK but other countries around the world. It was the South Asian communities in the Midlands and up north in England who pioneered the local VHS store where you could rent films. And we grew up, Omar and I, sort of a similar age, we grew up surrounded by the wealth of availability of films going all the way back from the 1940s, 50s to the latest releases from India. And these are the same stores that also stocked the latest Kung-Fu movies, the latest Hollywood blockbusters as well. So you get your Jackie Chan fix and your Ghostbusters (1984) fix at the same time as renting a Raj Kapoor film from the 1950s.

And I remember when my father brought a VHS player home, and it cost a huge amount of money in those days, in the early ‘80s. Working class immigrant families were prepared to save up and buy these extortionate players, but once you have it, you could rent all of these 50p, one pound films from your local store. We would be renting multiple films every week. And not just us, the entire South Asian community in my hometown of Leicester. It’s not just South Asians, but the Chinese community in Liverpool, the Turkish community in Berlin and in Germany, they were at the forefront of making this stuff available, importing the films from their home countries. So we grew up with that culture and it continued to some extent in the ‘90s and ‘2000s with DVD culture. Whenever I went to India, I'd always stock up on classic films on DVD and they'd be cheap and authentic versions, the proper published versions from the distributors with a little hologram on it to prove it wasn't a bootleg. They'd have English subtitles, and they weren't Blu-ray quality but they were still pretty good. They made these films accessible. They made these films continue to have a life. And that market has basically disappeared. I would say over the last 10, 15 years.

If you go to India now, all the chain stores, music and video stores, have pretty much disappeared. You can still get bootleg copies at your local grocery store and elsewhere, but they're very low res. We're basically talking about VCDs with YouTube rips, three films to a disc, that sort of stuff. So high quality versions for home video pretty much disappeared. Omar and I rely on those 90s and 2000s DVDs a lot to access this stuff. I even did a lot of screenings from DVDs because there's no other way I can get hold of the material. So I'm so thankful to those distributors that put this out. Really small and honest companies serving the immigrant communities in the UK that put out a particular film in ‘97 and now I can buy it off eBay. And if they hadn't done that, I wouldn't have been able to screen that film. And for me, there's a preservation aspect. I know there's a lot of folks these days in restoration, from analog sources, on making sure the prints are digitized. But there's an exhibition side, which I think has been lacking in terms of South Asian cinema, in terms of how do you preserve film culture, people watching this stuff at home, people sharing this, people having access to it. Because although streaming has made a certain amount of films accessible, a lot of people don't know the films exist on those sites. They don't know which films to watch. And you're still at the mercy of those films suddenly disappearing and not having access to them.

RES: In the US they're completely buried by the algorithms. They're impossible to find unless you search the exact title. You named your label The Cloud Door after a Mani Kaul short, is that indicative of the type of films you want to release, or do you aim for a wider scope from all genres of South Asian cinema?

RSR: Definitely wider. So we picked that name because we just love that film. And we thought it was a cool name. So it's not just art house. We're definitely looking at your mainstream Hindi films, your classics, your equivalents of a Singing in the Rain (1952) or Citizen Kane (1941) but the Indian versions, that level, but also documentary as well as fiction. And not just India, but Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh, and also the diasporic element. There are great British South Asian filmmakers and films from Germany, films from Canada and the US with a South Asian production element or cast that don't get the focus from other labels or pushed by distributors. And we want to make those films not only accessible on home video, but also easy to license if you're a film club or an indie cinema. So there's a dual focus there.

OA: We're not tied down to just independent art house films. But those films don't get the platform that they deserve. They just tend to circulate at film festivals and then they disappear into this abyss. We'd love to rectify that kind of situation. But yeah, we're here for all genres and the vastness of Indian cinema…the regional output is incredible. But a lot of those films, you just can't access them. Even the basics are not available, like Mother India (1957), Sholay (1975), the foundations of Indian classic cinema are impossible to even get hold of. Even when they do make the Blu-rays, I know there are Blu-rays of Sholay circulating, It's not done in a way the film really deserves. A lot of these films deserve proper artwork, booklets, audio commentary. That's what they really deserve.

But what I also say is that we've had really good involvement with India in terms of film preservation and the archive. So we've licensed Om Dar-B-Dar from the National Film Development Corporation and they linked us to the National Film Archive of India as well, we've been working together. The last decade there's been a push for film preservation. There's a lot of films that have been restored in either 2K or 4K. And also the Film Heritage Foundation was started by Shivendra Singh Dungarpur in India about seven or eight years ago. They're restoring a lot, up to nearly two films a year now.

RES: I was going to ask if you were talking to Film Heritage Foundation because I saw they just restored Sholay and screened it at Il Cinema Ritrovato. Have you spoken to them at all?

RSR: Yeah, Shivendra has been super generous with their time and very helpful with their contacts as well. So Shivendra in particular has hooked me up for a couple of screenings, for example. We haven't started negotiating too many extra films. We've got a short list and we've made contact with certain distributors and rights holders, but we really want to test whether there's a market out there. We feel there should be. By doing this Kickstarter on the initial release, it really helps to provide us some initial feedback as to whether there is a long-term possibility for this label. Because I think we've had a great response since we announced the launch of the label in January. But you only really know once you get orders or pre-orders whether it's viable or not. But definitely, we're talking to Shivendra.

Stuff that was restored a while back, to what Omar was saying, they only get the festival release. Take the first film on our label, Om Dar-B-Dar, restored quite a while ago, actually. And it had a release across India with PVR and it did well. Internationally it did a few festivals. Here in England it did the London Film Festival and that was it. Then it's not being heard of again. A lot of the archives and distributors, they're happy with the one off film festival screening. They're not really pushing it after that. And that's not how you build awareness of a film. That's not how a film lives on in people's hearts and minds. you've got to get it out there. You've got to screen it. And not just in big festivals, but in tiny little microcinemas and film clubs. That's how a film lives, I think. This is why it's important, not just to get this stuff out on home video, but also make it accessible at an affordable flat rate for a licensing as well.

RES: What led you to choose Om Dar-B-Dar to be your debut feature on the label?

OA: We chose this film because we feel very kind of passionate about it. When you watch Om Dar-B-Dar, your mind expands…I never expected this from Indian cinema. It's a bit of an urban legend in India with cinephiles. It was banned for a while and then it circulated through bootleg copies and it became subterranean and people would pass it along to each other, be it VHS and other screenings that would happen as well. So it got this cult status. But what I would say what's so significant about the film is that there are so many filmmakers working today that cite it as an important influence on them. So filmmakers like Anurag Kashyap, Imtiaz Ali, who's a very mainstream filmmaker, Kiran Rao even talked about how important it was on her filmmaking career as well.

So I think it's one of those films which has influenced a new generation, the next generation of filmmakers in India. A lot of people don't realize that internationally how significant this film is. And the director of Om Dar-B-Dar Kamal Swaroop was very much part of an experimental avant-garde that came out of Indian parallel cinema in the late ‘60s and ‘70s, going up into the ‘80s. So he trained and he worked as an assistant with Mani Kaul on a number of different films. So he was coming from a very experimental, creative background. That is a side of Indian cinema that audiences often don't see. It's a film that completely messes with you. It will just completely shatter your perceptions and the...understanding of what Indian cinema should be.

RES: Can’t wait to see it! You mentioned Parallel Cinema. So I want to discuss your new book The Revolution of Indian Parallel Cinema in the Global South, out now via Bloomsbury. Currently it’s only available in an expensive hardcover edition. Is there another version coming out that will be more accessible?

OA: Yeah, there's an accessible paperback version coming out early next year. I think it will be priced reasonably, about 13, 14 pounds. There's a case study in it on Kamal Swaroop and how important, significant that film was because it appeared much later than the avant-garde filmmakers who had made that kind of mark. So this appeared like a punch in the face to Indian cinema. It came out of nowhere. There's nothing quite like it in Indian cinema.

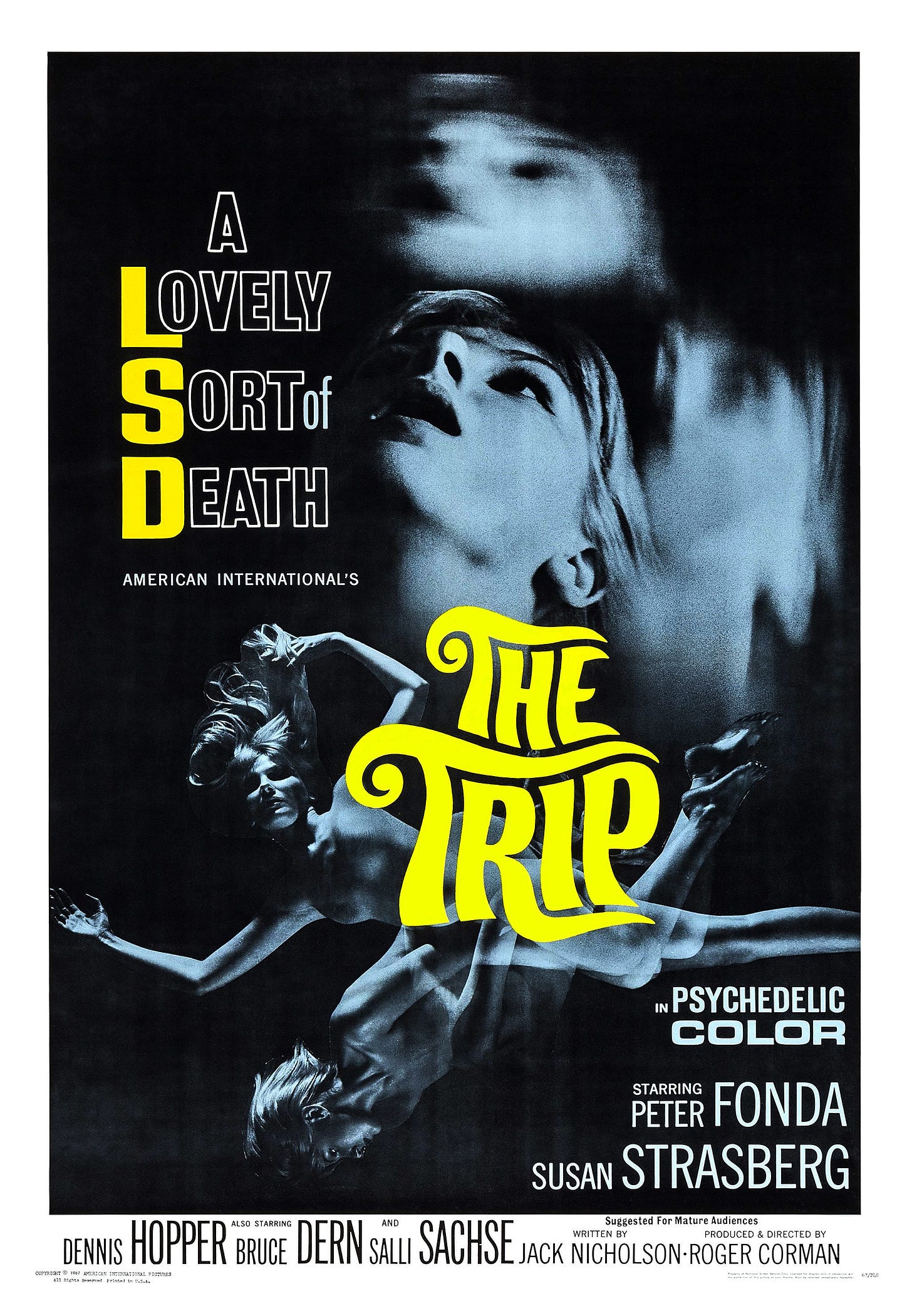

RSR: Yeah, it's one of my favorites. I screened it on a double bill with Roger Corman's The Trip (1967) because of the marketing. When it did the festival circuit, there was a pull quote on the poster that said this is the great Indian LSD trip. Because that’s the only way this non-classifiable film could be sold to Western audiences, to use that classic trip trope, like Kubrick’s “The Ultimate Trip” for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). But it is quite trippy, you do have to let go and let this film wash over you. It announces the label in the way that we want because it shatters expectations. It's no genre, but a thousand genres all rolled into one because it's funny, it's satirical, it's strange, it's got the art house element to it as well, but it's also very bawdy and very funny. It has ties to the modern day, it talks about the moon landings, part of it is set in the late 60s, but also hearkens back to mythology as well. So it's expansive in terms of its style and its content enough for it to be a bit of a statement film as well, in terms of our first release. Whether we picked correctly or not, time will soon tell, but it's certainly one that we feel passionately should be available and should not just be a cult film amongst filmmakers in India. It should just be a cult film full stop worldwide. And therefore, just to try and get it on home video would be a massive step forward to helping this film generate a name across the world, hopefully.

RES: Ranjit, could you talk about your background in film a little bit and then how you and Omar met and started working together?

RSR: I came to film a lot later than Omar, who's been steeped in this for many years as an educator as well as a programmer. For me, I was always a passionate film watcher and film lover ever since I was a kid. And because of that, I developed knowledge purely through voracious watching. But I only came to the programming fairly late in life. I started this film club called SUPAKINO, which actually started as a supporter of existing film clubs, independent cinemas, festivals, primarily in London. And it started off as a social media account, helping to promote this stuff, telling people what was on, posting about really good events and encouraging people to support local indie film clubs. But as a result of that, I got to know quite a lot of people in the exhibition sector in London. This is pre-pandemic. About eight, nine years ago when there was a mini-renaissance happening in London in terms of DIY film culture. And as a result of that, I got invited to do my own picks and introduce my own films. And I started out at a place called The Institute of Light, which was a proper hipster place in East London, the center of the DIY film culture at the time. My very first film programme was based on a series of films in which either the main character or a key side character wore a turban. And that was the only link between the films. So I started off screening the Bond film Octopussy (1983), at a venue under a railway arch. And that film has lots of train scenes in it. And you hear real trains rumbling above.

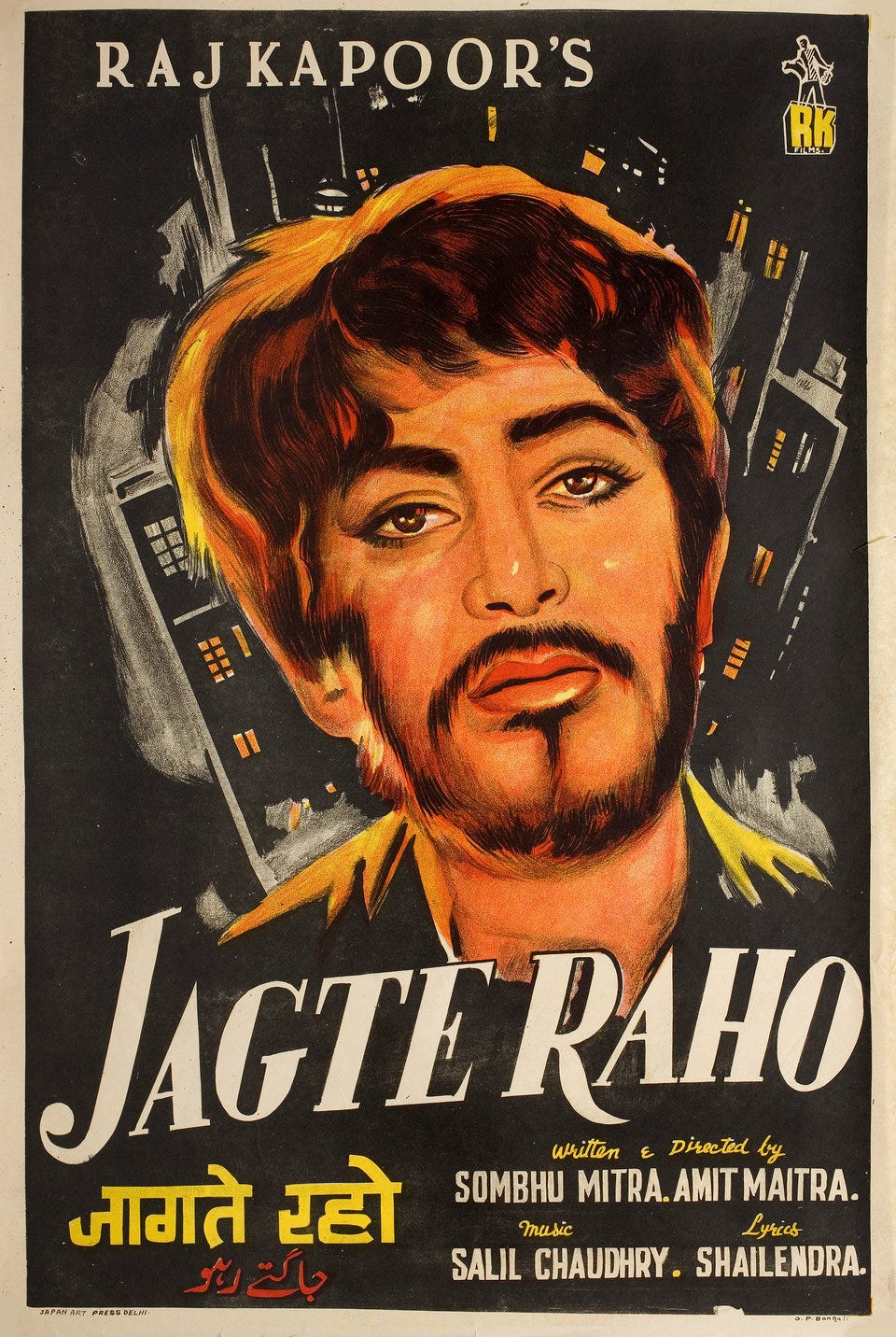

I went on to screen a whole bunch of them, culminating at the end with a two hour long clip show at the London Short Film Festival where I went through the whole history of the representation of Sikhs from early Hollywood to modern day YouTube, including documentaries and stuff. What started off as this fun thing that I did once a month on an evening or weekend, suddenly became quite important. And I made a lot of contacts with filmmakers and other venues that way. Omar and I connected via a programming season that I do called “Bombay Mix”, where I double bill an Indian film with a non-Indian film to try and mix audiences. Because what I found was, it was great, this sort of DIY culture springing up and filling the gap that the institutions and the big cinemas and the chain cinemas weren't doing. But the audiences weren't cross-pollinating or mixing in any way. So by creating these double bills where for example, I put a black and white Raj Kapoor film, Jagte Raho (1956) on a double bill with Scorsese's After Hours (1985), which are both films set in a single night with very similar themes. In one, a man just trying to get a glass of water and the other the man is trying to get home and then they both end up being chased by mobs and almost lynched. And I thought maybe the Scorsese audience would stay and watch the Raj Kappor. Maybe the classic South Asian Bollywood audience would give a lesser known Scorsese a go, just to try and mix those audiences. And so Omar and I got involved. Now, we've done a few, I invited Omar to introduce Om Dar-B-Dar on the double with The Trip, but also The Cloud Door which we screened on a double bill with the British ‘60s psychedelic film Wonderwall (1968). And we've got some more coming up. But also I was aware of Omar's brilliant work up in the north. So Omar's been programming not just Bollywood for quite a few years. Maybe you want to talk about that, Omar.

OA: I would always look at what Ranjit was doing in London and the kind of programming he was doing. It's very unique because I don't think that many South Asian film programmers and curators working in the UK are doing the stuff that me and Ranjit are doing. Why isn't anybody doing this more in the UK? My background…I was teaching film and media for 15 years in a sixth form college. Filmmaking, storyboarding, and film analysis. I did a PhD, a doctorate at University of Manchester. I stepped down and left my teaching role and went all in on research and going back to Indian cinema. That’s where it all started with film curation. Manchester is smaller than London in terms of the audiences and the cinemas and what's available there. So Home, which is the cultural cinema home in Manchester, I went to them with the idea of not just Bollywood, but showing different independent, marginal and alternative films. So films like The Lunchbox (2013), Anurag Kashyap’s films as well, lots of really interesting films that are coming through.

Each year we've kind of done a different program around a different theme. So we've looked at things like caste, representation of women. That kind of spiraled into other things. So I've done more kind of curation now over the last few years. So in 2021 I did a strand for Il Cinema Ritrovato, in Bologna, which was on parallel cinema, co-curated with Shivendra Singh Dungarpur and Cecilia Cenciarelli. That was quite significant because it was the first major kind of retrospective of parallel cinema in over 30 years in Europe, and culminated with the restoration of Govindan Aravindan’s Kummatty (1979), which was supported by Martin Scorsese's Film Foundation. And then over the years, me and Ranjit being in contact, he invited me to many of his kind of things, the “Bombay Mix” that he's programmed as well. And we got talking, sharing ideas, contacts, networks. So it's been a really important collaboration.

RES: You both seem to be avid collectors. So in starting the new label, what do you want The Cloud Door to be emphasizing in terms of the physical product?

RSR: I mean, we love what the boutique market is doing at the moment. Some really good stuff out there. We definitely want to get artists involved. What's their response to the film…custom artwork…we want the slipcover for this. We've got a really great Polish film poster artist involved who's done a couple of my events in the past. Really beautiful designs. He went to a Polish film poster school, illustration, he takes forward that sort of classic design, those alternative posters from the ‘70s and ‘80s into the modern day. I've done this for non-Indian films, for some of my events. I like the idea of applying that classic Polish film poster design to a film that wouldn't necessarily get that poster. So to have that poster. I think it's a great combination for Om Dar-B-Dar, because hopefully he'll come up with something amazing and abstract. So we want custom artwork. We want it to feel like a premium product. And in terms of the extras, we have the director, Kamal Swaroop, lined up to do an audio commentary. We've got his son, who's also a filmmaker, lined up to help us with cast and crew interviews and some additional behind the scenes material. We want to have great packaging design as well. So one of the screenings I did, I met someone in the world of branding and we've got him involved. Some of this stuff is actually as a result of our curation, people that we've met along the way.

We know Omar as part of his curation, he's written essays for other labels’ booklets, and thereby we've been able to use those contacts to help us in terms of, well, how do you manufacture a Blu-ray? How do you actually author it? And what are the steps to create a physical product? So between the two of us, we've managed to figure out all the different steps for creating it. And in terms of what we care about, we definitely care about these releases being given the same love, care and attention that we see other boutique labels giving other films. And I think that's been very much lacking in the South Asian space, because even when you are getting things on Blu-ray or DVD, they're not particularly focused on the package itself and the extras and the design. And we love that stuff.

RES: It’s hard to find that balance of making a premium product at an affordable price point.

RSR: Yeah, we won't go as far as, at least not for the first release, using the special metal boxes and all that sort of stuff. But we've been looking at labels…I like the Canadian International Pictures ones that get put out on Vinegar Syndrome. Omar, I know, you like the A24 releases…

OA: Radiance, Criterion…really good. We want to do this right, because I've realized as a collector and probably Ranjit and yourself as well, is that as collectors, you're quite savvy, in terms of the packaging and the booklet and what's being put in front of you. And if it's not correct…that first impression is really important. Does it meet that standard? And we feel that it does. But I think with the Kickstarter, the initial cost right now in terms of pre-ordering the Blu-ray is a little bit higher only because we need that for the startup costs of setting up the label. After that, we're going to definitely try to come back to the levels that most premium boutique labels are charging as well.

RES: It seems like the UK has a really robust boutique home video scene. Have you found support there?

OA: Yeah, I did speak to to Fran Simeoni from Radiance quite a bit about the ways in. How do you go about doing this? Where do you start? He was massively generous with his time and gave some really important pointers in terms of the way forward. The boutique home video market in England is growing. Radiance, Second SIght, Second Run. Second Run has been really important for us because they've been one of the few labels that have tried to put out South Asian titles. Mehelli Modi has been very supportive behind the scenes in terms of what we're doing with the label. They recently released Thampu (The Circus Tent, 1978), which was an Aravindan Govindan film. And there was another one, Ishanou (The Chosen One, 1990), which was a Manipuri film by Aribam Syam Sharma, for which I wrote the booklet and was just released by Second Run as well. And I know they've got other parallel cinema films which have been restored by the Film Heritage Foundation, which they're going to release in the future as well. So I think Second Run has been one of the few labels who have managed to put out South Asian film titles. It is a bit of a head scratcher even to this day why we're in this situation and I find it really puzzling and baffling why all these labels around the world, now you've got labels literally in all these countries, incredibly big labels but nobody wants to do anything.

RES: My anecdotal impression, talking to people who have tried, is that Indian distributors are not interested in putting their titles out on home video, at least for new releases. They make their money pre-selling to streamers and they're good. But if you released RRR (2022) in a loaded 4K UHD release, that's going to sell huge, to pick a title that really crossed over here. I don't know if you've had similar reactions.

RSR: Yeah, not just new, any films. And actually not just home video, but they're not even interested in having them in the cinema. So this is the other puzzling thing. And let's not just blame Indian distributors. I've had that from some Italian and French distributors as well. There are certain license holders out there that they're just happy with streaming plus the odd several thousand pound festival funded screening, where they just get a one-off bonus basically. And they're not interested in putting the work to get their film out in 100 independent small cinemas of only 40 seats or 70 seats. They're not interested in the work required for what they see as very little.

And I think that's probably taking the longest time. For a start, we have day jobs. We've got our curation as well. So we've been trying to fit this in the evenings and weekends over the last year and a half. But the longest amount of time has been just cracking open that door to archives and rights holders, trying to educate them on the economics of film exhibition and home video because it's not an area they really understand. And we've got a crack open now with NFDC now part of NFAI, National Film Archive of India. I think they finally sort of get what we're doing. And that's been a real positive, actually, that they're willing to sort of come on board with this, because they have a wealth of films in their archive. And if this first one is successful, that gives us access to potentially plenty more. But it is a different model. It's just not a model they are used to.

OA: It's worth saying that it's not like boutique labels haven't tried. If you look at Carlotta in France, they released quite a lot of Indian films…I've got a number of their DVDs. I got the Guru Dutt stuff on DVD from there. There have been attempts. Eureka’s Masters of Cinema line here in the UK, they tried on Satyajit Ray with Abhijan (1962), which they released on DVD. I remember speaking to them and they said, well, it just didn't sell. And admittedly, Criterion have been quite poor in my opinion, because all they've done is just Ray. I think it's weird because of their positioning in the boutique label market and what they have access to. I'm surprised that they haven't pursued more Indian titles. It has really surprised me, but it's also been really disappointing that it's consistently been like that over the last 10 years or so.

RSR: It's very easy to just give up on this stuff. because it is so difficult. It is difficult to track these distribution goals down, difficult to negotiate them, it's difficult to carry on being motivated to talk to them when you hit brick wall after brick wall. And so when you do finally get through, we want to make a statement, say that these films are worth the same love and attention you would like a cult film from the US or a classic film from Japan or some great Antonioni film from Italy. They are the equivalent. And it's only by doing it in this way that I think we can get that message across. Then hopefully the label has legs and then we can then put out a range of films. But that's the sort of statement we're trying to make with this first release and hopefully the next few as well.

RES: This is why your label is so essential! Before we go - can you both recommend an Indian film that not enough people know about? Can be anything…

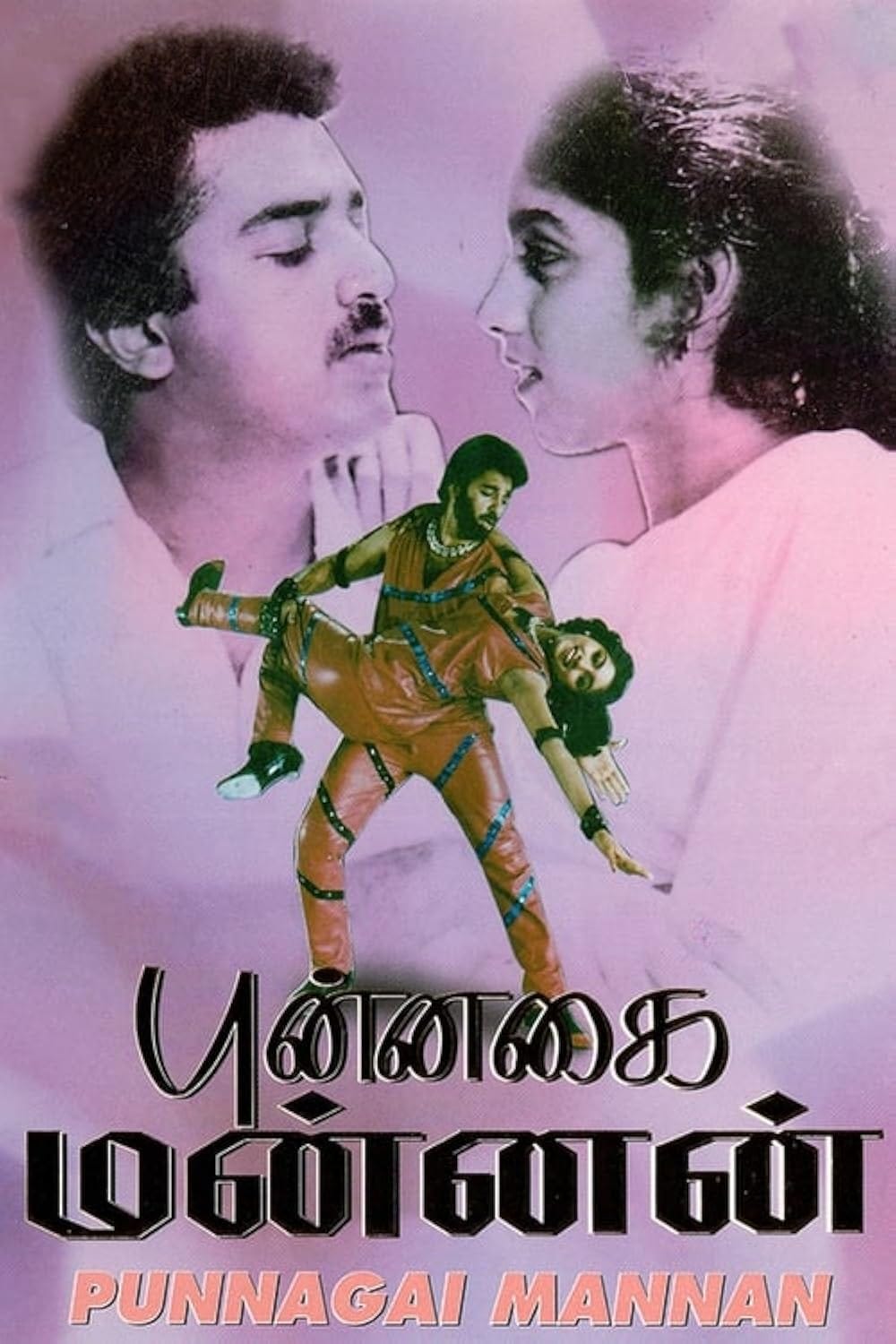

RSR: Well, only because I was listening to the soundtrack this morning. There's this great South Indian film called Punnagai Mannan (1986), it's a Kamal Haasan film from the mid-’80s. And it's got this great electronic synthesizer soundtrack by Ilaiyaraaja. It was dubbed into various other Indian languages as well. So it's also known as Dance Master and Chacha Charlie, Chacha meaning uncle. Haasan plays a double role. The main role is as a disco dancing teacher, and also plays his own uncle, who due to some heartbreak in his past, takes to dressing and acting like Charlie Chaplin. It's fun, but it's very dark. So yeah, check that out, I think it’s on YouTube.

RES: I need to dive deeper on Kamal Haasan! I love Pushpaka Vimana (1987), his dialogue-free tragicomedy, and his Mrs. Doubtfire remake Chachi 420 (1997). I also really liked Thug Life (2025), even though nobody else did…

RSR: I haven’t seen that, or even some of his classic ‘90s stuff. I remember why I watched that one, it was because I did a double bill of Modern Times (1936) and Shree 420 (1955), where Raj Kapoor does a sort of Chaplin-esque type of character. And I showed a clip from Punnagai Mannan, which I think means King of Smiles. And I showed a clip of that because of the Charlie Chaplin connection. So that's why I watched it.

RES: It sounds amazing. Omar, does anything come to mind for you?

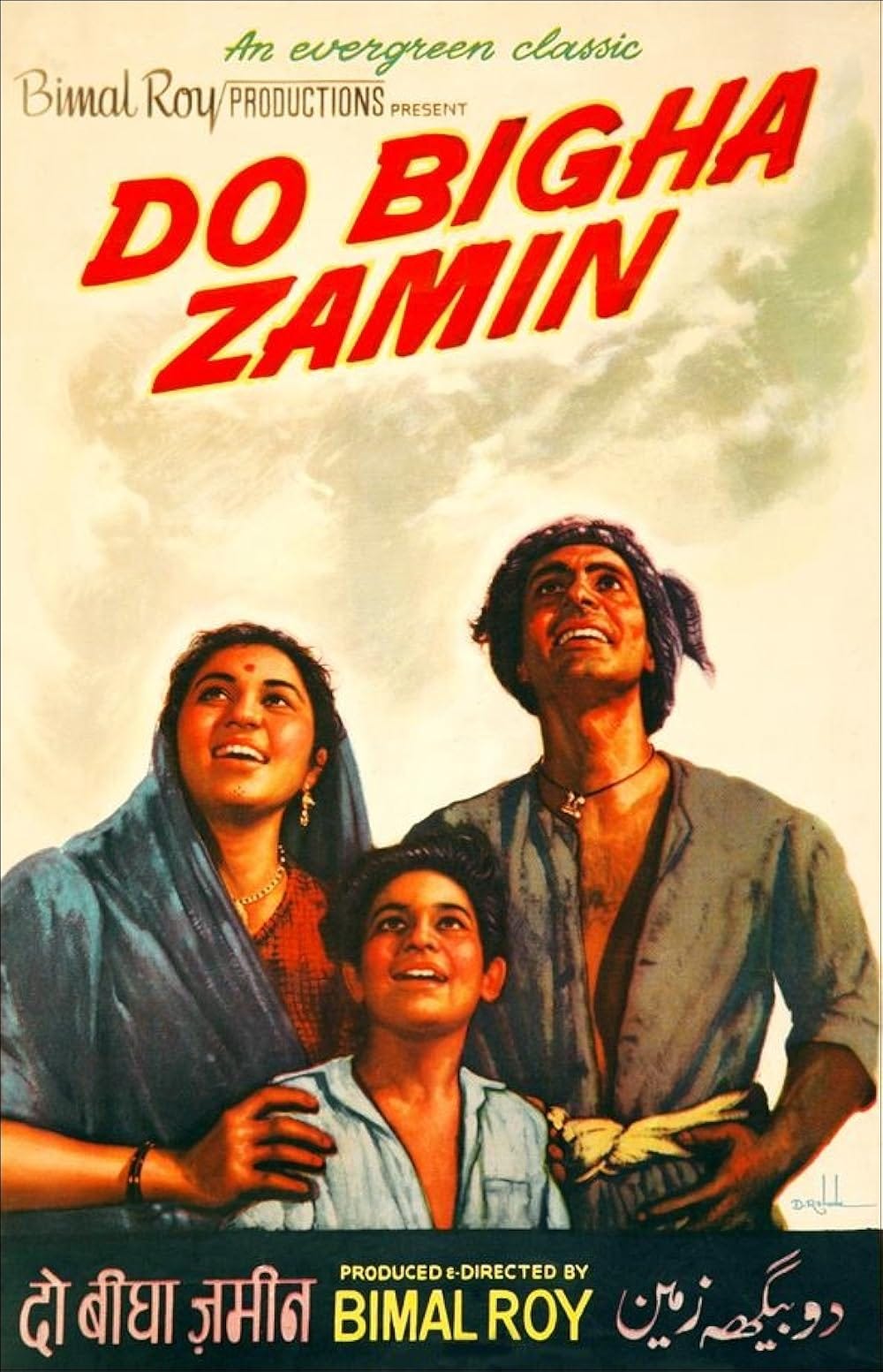

OA: You’re putting me on the spot now! one that I always keep going back to is Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin (1953). It's one of the films that's often cited as being an example of Indian neorealism, but it's a brilliant film in terms of the way which it critiques capitalism along with everything else. It's got one of the most pessimistic, downbeat endings I've ever seen for a mainstream Hindi Indian film. Whenever I watched it, I thought, how did he even get away with ending on this note? It's about the trials and tribulations of a farmer who's in debt, forced to go to the city and works pulling a rickshaw through the city, and his son accompanies him and sees his father self-destruct. It's very similar in terms of the narrative to Bicycle Thieves, to De Sica’s film, which influenced Bimal Roy’s approach in the story as well. So I think that is really important. a really foundational film in terms of Indian cinema. But can you get it? No. It's on a poor DVD somewhere. I do know that it’s been restored.

RSR: It makes my pick pale in comparison!

OA: Not at all!

RSR: He picks a foundational film of Indian cinema and I pick Chacha Charlie from the ‘80s [laughs]!

RES: This is what makes you two a good team, you span the full range of cinematic experience!