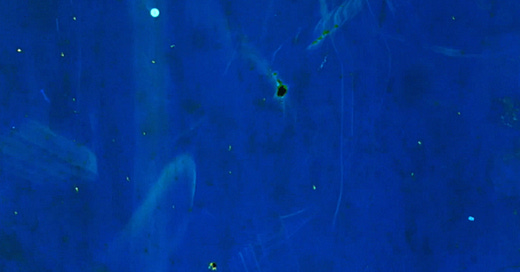

sound of a million insects, light of a thousand stars (2014, Tomonari Nishikawa)

I first met Tomonari Nishikawa at SUNY Binghamton in 2001, where both of us were double-majoring in Cinema and Philosophy as undergraduates (our future wealth secured). He had such a cherubic appearance I had no idea he was over a decade older than me, and had already lived a full and peripatetic life. As he recounted to Katy Martin, he majored in Economics at a Japanese University before he started ditching class to see Art Theater Guild films, eventually dropping out with a plan to study cinema abroad. He raised money working as a truck driver, on a nursery farm outside Sydney, and at a youth hostel in Perth. This circuitous path led him to the affordable redoubt of Binghamton. He was initially disappointed that it didn’t offer traditional directing or screenwriting classes, with its faculty (including Ken Jacobs, Ariana Gerstein, Vincent Grenier (RIP), and Julie Murray) focused on experimental practices. But he was soon taken with the creative opportunities they offered:

I worked as a Teaching Assistant for Vincent's video-making class, and I learned a lot from him about interpreting cinema, composing in time, and articulating ideas through moving images. Ken Jacobs was the one who probably influenced me the most. He started my great interest in cinema apparatus, and making abstract forms from representational images.

I came to Binghamton straight out of a Buffalo-area high school (Go Amherst Tigers), and adjusting to living on my own for the first time. Tomo was calm, assured, and focused where I was…not. This carried over to the classroom, where he was working through various styles - like his hand-developed abstractions that would turn into his thesis film Apollo (2003), and the single-frame in-camera edits of his Sketch Film series (2005-2007). I was making clumsy found-footage montages and jokey relationship comedies that should remain buried in my storage unit forever. It was no surprise that his work started appearing at major festivals, and that he secured a job as a Professor at SUNY Binghamton.

After I moved to NYC for grad school I would keep an eye out for his work - at the New York Film Festival, Migrating Forms, Prismatic Ground, wherever I could find it. And though we were never close friends at Binghamton (I ran with the radio station misfits at WHRW), when we ran into each other we had an easy rapport as if no time had passed. I bumped into him while hungrily walking to a Pizza Hut at the 2008 Rotterdam Film Festival, and it felt like we were back in the bowels of Binghamton sweating over a Steenbeck. As our lives further diverged, we fell out of touch, but the news of his sickness and then his death hit me with waves of sorrow. He was the best of us, and now he is gone.

Watch his films. Support his family. Binghamton University will hold a memorial on May 4. And there will be a student led screening of his works in Lecture Hall 6 on Friday May 2.

I reached out to teachers, friends, colleagues, artists, programmers, and film critics whose lives were touched by Tomonari Nishikawa. Their words are below.

Apollo (2003, TN)

“92 next month but old age loses its charm when I hear news like this. Tomonari was always young!”

- Ken Jacobs, Filmmaker

“Tomonari was a sweet, young, and energetic person when I met him in San Francisco at the beginning of the century. I liked his films very much. Really sad to hear of his passing. I wish his family the very best.”

- Ernie Gehr, Filmmaker

“Tomonari's calm, humble, and playful demeanour belied the fact that he was unquestionably one of the finest talents of his generation. His films were consistently great, which made him a regular at Wavelengths where his presence was appreciated by all who encountered him. Friendly and good natured, he was also precise and generous —a natural teacher and leader. While tragically cut short, his body of work has altered the history of avant-garde cinema and will be influential well into the future. So will his beautiful spirit.”

- Andréa Picard, Senior Film Curator, Toronto International Film Festival & TIFF Cinematheque

“My memories of those few years teaching at SUNY Binghamton and the people I met are warm and vivid. I was in close conversation with Tom as he worked on his thesis film, Apollo. His method of approach seemed immediately precise and at the same time left plenty of space for chance and delightful accidents. I think his sense of humor played into his discoveries in hand processing too; in the conjured cosmos of photogrammed soap bubbles, the effect of heat and household chemicals on emulsion and visual witticisms slipped in amid a frenzy of images. He honed an exquisite tension of pattern and chaos, refining it to startling effect in subsequent works. I would run into Tom regularly at various festivals around the country in the years that followed and was always excited to see new ideas unfold in his meticulous process. I'm sad he has been taken from us.”

-Julie Murray, Associate Director, Film and Video, CalArts

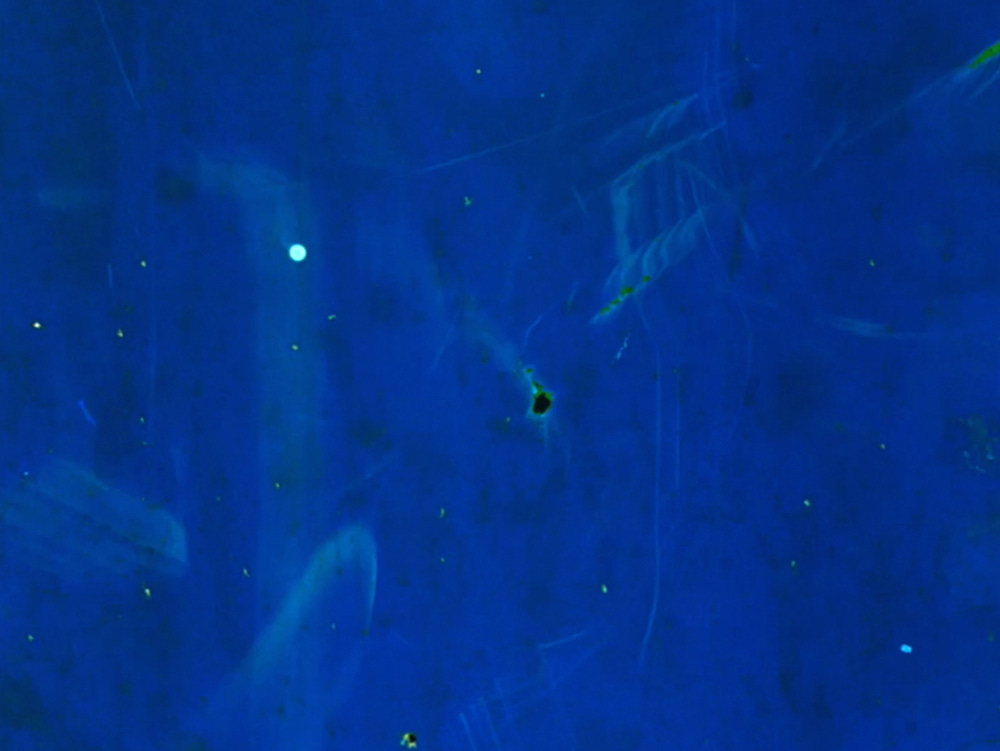

“Tomo showed two films at Prismatic Ground last year— Light, Noise Smoke, And Light, Noise, Smoke and his latest live looping performance, the third in a trilogy, Six Seventy-Two Variations, Variation 3 (For Charles). He was an incredibly talented and precise filmmaker, who created beautiful experiences with a very thorough, diligent conceptual and technical sensibility, and beyond that he was a very kind person. We corresponded a little after he found out he was sick. I had this half-baked idea of starting a “Prismatic Ground 16mm Archive”, which is currently a mini fridge in my apartment, and asked if he wanted to contribute anything. He very kindly sent the resulting film of one of his performances, and picking it up again yesterday just about broke my heart. I’m attaching a few pictures— the performance is from last year’s Prismatic Ground, at Anthology Film Archives.”

- Inney Prakash, Curator of Film at Asia Society and founder of the Prismatic Ground Film Festival

“Tomonari was a visionary - an amazing, singular artist - and one of the kindest, most supportive people I have known. He will be remembered and missed forever.” - Michael Robinson, Filmmaker

“Tomo was such a kind person and I loved his film experiments.”

- Laida Lertxundi, Filmmaker

Tomonari Nishikawa at Anthology Film Archives, May 10, 2024 (courtesy of Inney Prakash)

“It was very moving to see the outpouring of support for Tomonari over the last few months. We work in a very small field, but to see how much he meant to people all over the world was inspiring: people inspired by his films, his teaching, his research, his presence. We were artistic colleagues—our films inspired each other and I will miss both the creative push of seeing a new work by him and his own curiosity that he had about the work of others. "It’s interesting”, was always his dry comment, a catch-phrase that belied the expressive beauty that resonated out of his focused, precise films.”

-Chris Kennedy, Filmmaker

“Several years ago, I had the opportunity to write about Tomo’s Sound of a Million Insects, Light of a Thousand Stars (2014), a remarkably beautiful film for which Nishikawa secreted 100 feet of 35mm negative film, as he told me, “under fallen leaves alongside a country road”– a fairly anodyne description which belied the location’s proximity to the Fukushima Daiichi power plant, the site of a 2011 nuclear disaster. The resulting film is a thrumming, lapidary blue, and it remains one of my favorite colors I’ve ever seen projected. I admired Tomo’s willingness to seek out such an unusual, and even risky, spot to make his art, and in our correspondence about the work, he and I agreed that it served as an abstract documentary of a place, created in a mode of "poetic reportage.” He happily and readily shared a file of the film with me to show at talks, in classes, and at screenings. I will always be grateful for his artistry, generosity, and willingness to engage seriously with those who love his work.”

- Gregory Zinman, Associate Professor, Dept. of Film and Media, Emory University

“As a filmmaker, Tomonari continuously found new and creative ways to explore the possibilities of cinema, and his support and generosity for other filmmakers was unparalleled.

- Ryan Marino, Filmmaker

Tomonari Nishikawa at Binghamton University (courtesy of Ariana Gerstein)

“The impressions Tomonari has left on me will never leave. I will return to them always to remember and learn. There I can find a dogged work ethic, creative questioning, wide generosity, and a truly fascinating combination of unrelenting determination with gentle humor. He was an amazing colleague and friend. We mostly discussed the Cinema Department at BU, but sometimes we shared stories about our kids and parenting. I can say with confidence that he was an amazing father to his three kids. I have high hopes for those kids! And his wife Miki is a pillar of strength. I know that she will help them remember their Dad as they grow.”

-Ariana Gerstein, Professor and Graduate Director, Department of Cinema, Binghamton University

Shibuya-Tokyo (2010, TN)

“When I first saw Tomonari Nishikawa’s Shibuya - Tokyo (2010), it was clear I was witnessing an explosion of styles that defied neatly contained terms or traditions. The film traces twenty exits from the Japanese Railway Company’s bustling Yamanote Line and captures one of the most recognizable and chaotic urban centers in the world—Shibuya Crossing—with a formal control that verges on incantation. Using 16mm film and a single-frame shooting technique, Tomonari exposed the same piece of film multiple times in-camera—a process that leaves no room for error, no digital safety net, no second chances. With a kind of monastic discipline, bodies graze the screen like ghosts—appearing and vanishing into a pulsating crowd. Fragments of movement, architecture, and gesture erupt into a temporal palimpsest. In this film, and in Tokyo – Ebisu (2010), he seemed to be asking: how much can a frame hold before it dissolves into light?

Many of Tomo’s films hovered at that razor-thin edge between control and surrender. He would go on to explore everything from Times Square—captured in 45 7 Broadway (2013), a black-and-white film shot through three colored filters and optically printed onto color stock—to burying 100 feet of 35mm film in the irradiated soil surrounding the Fukushima Power Plant (sound of a million insects, light of a thousand stars, 2014). As exacting as his processes were, they never felt like acts of manipulation. They felt more like delicate negotiations, invitations for the medium to speak in its own voice.

I met Tomo several times at festivals over the years, always struck by his warmth and humility—striking qualities given the weight his films carried among those of us working in and around experimental film. But it wasn’t until I began teaching at Binghamton University that I understood the full scope of his care—not just for film, but for the people around him. He taught, chaired the department, mentored students, navigated institutional demands, supported colleagues, and raised a family—all with a quiet steadiness that never sought attention.

What left the deepest mark on me personally were his check-ins with faculty—a gentle form of stewardship that felt quietly radical in its mission to create a truly engaged department. He carved out time for these informal, unassuming conversations. In a profession that so often rewards performance over presence, Tomo made us feel noticed, held, and looked after—not because he had to, but because that’s who he was. For many of us, those check-ins were a lifeline: subtle, steady reminders that we weren’t alone, and that we were seen.

In every case, those conversations would inevitably veer into larger questions—about pedagogy, about how to witness the media landscape our students live in, and how to shepherd them through the thinking that has shaped its past. At this, Tomo was a quiet master.”

-Eli Horwatt, Lecturer, Department of Cinema, Binghamton University

45 7 Broadway (2013, TN)

“I believe I met Tomonari in Toronto sometime in 2011 or 2012. I admired him as a filmmaker and he was just as lovely as a human being. We always enjoyed hanging out whenever we were in the same town. Every time we met up, we picked up from where we left off. We confided in each other, about family, about living. We shared a grotesque fascination with bad Japanese food outside our homeland. Tomo inspired me as an artist as well as a father. Always encouraging, thoughtful, generous. When he brought me to talk at Binghamton in 2023 Tomo told me he’d started teaching himself automotive repair. He was consistently upbeat about his prognosis. We’re worse off without him. I wish I had more time with him, I wish we all had more time with him. I wasn’t able to attend his last set of performances in NYC and I wrote him apologizing and he said it was ok, there’s always next time. Then he made a joke about NYC parking.”

-Joshua Gen Solondz, Artist

Ten Mornings Ten Evenings and One Horizon (2016, TN)

“Every time a car passes through the vertically segmented frame of Ten Mornings Ten Evenings and One Horizon, flickering into being and then driving off into oblivion, reminds me of the Venerable Bede's story of the sparrow in the banqueting hall:

The present life of man, O king, seems to me, in comparison of that time which is unknown to us, like to the swift flight of a sparrow through the room wherein you sit at supper in winter, with your commanders and ministers, and a good fire in the midst, whilst the storms of rain and snow prevail abroad; the sparrow, whilst he is within, is safe from the wintry storm; but after a short space of fair weather, he immediately vanishes out of your sight, into the dark winter from which he had emerged. So this life of man appears for a short space, but of what went before, or what is to follow, we are utterly ignorant.”

- Mark Asch, Film Critic

“With the passing of Tomonari Nishikawa, the experimental film community has lost one of its great ambassadors, a beneficent and inspiring presence whose remarkable films were shaped by deeply considered procedural principles and innovative material interventions. After news of Tomo’s death began to circulate, a few friends reached out to share with me how much he had meant to them. All of us had been inspired by our experiences of Tomo’s work, but one common social thread in our recollections was that he had taught and programmed our work and had helped its circulation. Such goodwill is all too rare in creative communities, and Tomo’s was an example to live by. His commitment to community was earnest and selfless - through his films and performances he wanted to make possible new and innovative visions, and in his giving exchanges with his peers, he facilitated and encouraged our work.”

- Stephen Broomer, Filmmaker

Lumphini 2552 (2009, TN)

“I’m not sure which of Tomo’s films I saw first, but I was already quite familiar with his work—so meticulous in its construction and so lucid in its exploration of cinematic processes. He seemed to me the model of a film artist, working out intricate puzzles for himself through a materialist and thorough method. When I finally met him, I encountered a person as attentive and generous to others as he was thoughtful in his own practice, soft-spoken but forthright and engaged, committed to cinema as both art form and community. I recall when I went to interview for a job at Binghamton—I was quite green and nervous and felt the creep of Imposter Syndrome that is built into such rituals. Tomo gave me a little tour, brought me to the cafeteria for a coffee, showed me the legendary Serene Velocity hallway, and set me at ease. It was a quiet moment in a day of so many stresses and distractions—needless to say I didn’t get that job—but however rote that moment was for him, it meant a lot to me. I’m sorry we didn’t get to share more moments like that—ideally with me being as attentive and sensitive as he was. But I’m grateful for his exceptional body of work, which I share with my students whenever I can, and I’m grateful to have known and learned from him.”

-Leo Goldsmith, Assistant Professor of Screen Studies, The New School

“Tomonari was one of the most meticulous, open-minded, and unique filmmakers of his generation. His work was influenced by structural film, as well as the history of the Japanese avant-garde. His work was about paying close attention to small parts of everyday life -- bridges, buildings, Ferris wheels and fireworks -- and recovering a sense of wonder about them. Great artists are able to channel our perception and make us see the world anew, and Tomonari was the very definition of a great artist.”

-Michael Sicinski, Film Critic

Light, Noise, Smoke, and Light, Noise, Smoke (2023, TN)

“The shock of my first experience watching Tomonari's 2014 film sound of a million insects, light of a thousand stars, its two-minute runtime nearly buried within a feature-length shorts program, will likely stand out in my mind for a very long time. I never had the privilege of meeting Tomo in person, but I loved everything that I ever knew about him. The tone of his e-mails was always humble and gentle, and I got the sense of him being a beautiful person, in addition to being a wonderful filmmaker. I thank him for inspiring me and others by being both.”

-Aaron Cutler, Programmer and Film Critic

Aaron Cutler’s 2017 interview with Tomo, discussing his process shooting Ten Mornings Ten Evenings and One Horizon (2016) [RES]:

“The project came to mind when I found out that the river’s source was in my father’s birth village,” says Nishikawa about his latest, ten-minute film, which he shot on color 16mm. “I thought that it would be interesting to show a series of shots of the river as a metaphor for life’s journey, then came up with the idea of shooting bridges as markers of certain moments in time. I decided to shoot in the morning and evening with masking and multiple-exposure techniques that I hoped would enhance the sunrise and sunset, as well as cohere shots registered across different locations. I ultimately photographed ten bridges, each of them twice—once in the morning from the east side, and once in the evening from the west. I tried to always capture the entire bridge within the frame. The film gradually progresses from medium to extreme long shots as the river widens on its way to the ocean. The sounds throughout most of the film come primarily from water, from birds, and from offscreen vehicles; at the end, though, a small aircraft is heard, encouraging audience members to look up at the sky.”

“Deeply saddened to learn of the passing of Tomonari Nishikawa today. Tomonari was an extraordinary filmmaker, teacher, and human being whose presence left a deep and lasting mark on everyone privileged enough to know him.

I first met Tomonari in 2004, during his time in the Master of Fine Arts program at the San Francisco Art Institute. Over the years I spent working with him—in tutorials, in Film History, and in our Graduate Critique Seminars—I came to know a mind that was endlessly curious, deeply inventive, and fiercely committed to his craft.

Tomonari was not just a student of film—he was a student of the world. He approached his work with a remarkable spirit of experimentation and originality. Whether building pinhole cameras from paint cans or turning slits in video lenses into tools for poetic vision, he never feared venturing into the unknown. He welcomed complexity and reveled in the small, meticulous details others might overlook. His work wasn’t just technical—it was soul-driven, full of quiet power and integrity.

But Tomonari’s brilliance was not confined to his art alone. He was also an engaged and generous member of his community. He brought energy and thoughtful insight into every discussion, whether in the classroom or during a departmental search committee. He listened carefully, he questioned with clarity, and he cared—deeply—about shaping the spaces he was part of.

What stood out most about Tomonari was his perseverance. Before starting graduate school, he spent a year working on a factory assembly line in Japan—choosing hard labor over debt, determination over comfort. Even while working long hours in the maintenance department at SFAI to pay his tuition, he remained one of the most productive and celebrated students in the program’s history. It was no surprise when he received the James Broughton Award, the highest honor the Institute bestows upon a film student.

His student work spoke for itself. From his film Apollo, featured in a major survey of Japanese independent film at the Pacific Film Archive, to Sketch Film screened at the New York Film Festival, to Market Street honored at the San Francisco International Film Festival—Tomonari’s vision resonated across cultures and continents. In the passing years, he become a defining voice in contemporary independent cinema, and even in his too-short life, he accomplished so much.

He was also a gifted teacher. Whether formally or informally, Tomonari gave selflessly of his time and knowledge. I remember a student telling me how he once spent five hours explaining the workings of an optical printer, simply because he cared. That was who he was—passionate, present, and profoundly generous.

Tomonari Nishikawa embodied the very best of what it means to be an artist, a mentor, and a human being. His work lives on, and so does the quiet strength, curiosity, and grace he brought into this world. He will be deeply missed, but never forgotten.

- Janis Crystal Lipzin, Artist

“Nishikawa's two-minute marvel SOUND OF A MILLION INSECTS, LIGHT OF A THOUSAND STARS is the shortest film ever to win top prize from a jury upon which I've served (the "Explora" section of Curtocircuito shorts festival, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, October 2015.)

The festival chief was very surprised that we went for what was by some way the shortest film in our competition. But as Hans Hurch always used to say "film is film," and the point about duration is not its extent but how the artist elects to use it. This film is the length it is for a specific reason, and it's the perfect length.

The Spanish press reported that our jury composed a haiku instead of issuing the usual "motivation" text. This wasn't quite correct! In fact we excerpted part of Tennyson's 1830 poem "Nothing Will Die," which is now perhaps best known for its shattering use at the end of THE ELEPHANT MAN. The stream flows, The wind blows, The cloud fleets, The heart beats, Nothing will die.

世の中を明るくした西川智成さんを偲んで。“

- Neil Young, Film Critic and Programmer

I met Tomonari at SFAI when I was a Visiting Artist (MFA, SFAI, 1979) and can add only a little to Janis Crystal Lipzin’s heartfelt and personal tribute. She described him fully and intimately. I enjoyed working with him - so curious and immersed in the essence of filmmaking and willing to take light, time and motion risks. His film “Down Market Street” used the basic elements of 16mm film - 24 frames per second to make a brilliant, scintillating, and unique portrait of that time and street in San Francisco. He made me smile. Bravo, Tomonari.