Tamil director Karthik Subbaraj loudly declares his influences, dedicating the dizzying gangster Western Jigarthanda DoubleX (2023) to Clint Eastwood, Rajinikanth, and Mani Ratnam. Ratnam is the grand old man of Tamil cinema, a highly decorated director of expressive melodramas whose career spans five decades. They both have new features that opened within a month of each other - Subbaraj’s kinetic genre mashup Retro (opened on May 1st, now on Netflix) and Ratnam’s highly anticipated reunion with megastar Kamal Haasan entitled Thug Life, which opened in theaters on June 5th (they first worked together on the canonical mob movie Nayakan in 1987).

Subbaraj’s filmmaking career began as a contestant on the reality TV show Naalaiya Iyakkunar (2009-2020), similar to Project: Greenlight except for shorts instead of features. It was a remarkable incubator for talent, which Subbaraj has compared to the French New Wave, including megastar Vijay Sethupathi (Viduthulai, Maharaja) and director Ashwath Marimuthu (Dragon). Subbaraj told The News Minute that he might still be a software engineer if not for the push it gave him into the arts. In each season the contestants would make 7 short films in 7 different genres, a prompt that seems to inspire Subbaraj to this day, whose films seek to fuse every possible genre into a gesamtkunstwerk of masala film.

His debut feature is the head-spinning horror-comedy-thriller Pizza (2012), which stars Sethupathi as a pizza delivery man who may (or may not) get trapped inside of a haunted house with his boss’ possessed daughter. Its rug-pull plot twist delighted audiences, deploying the stylistic vernacular of horror, complete with jump scares, while seamlessly shifting tones into a class-conscious caper flick. It also marked the first collaboration with ferociously talented composer Santhosh Narayanan, who has gone on to score all of Subbaraj’s films. Subbaraj has continued his playful experiment, including the boisterous filmmaking satire Jigarthanda (2014), the no-dialogue thriller Mercury (2018), a dip into “mass” (or blockbuster) filmmaking with the Rajinikanth starrer Petta (2019 - and for more on Rajini please read my career deep dive). During early drafts of writing Retro, Subbaraj had Rajinikanth in mind to star, but as it expanded the character kept getting younger, and so the part went to Suriya, who sports a beautiful fu manchu.

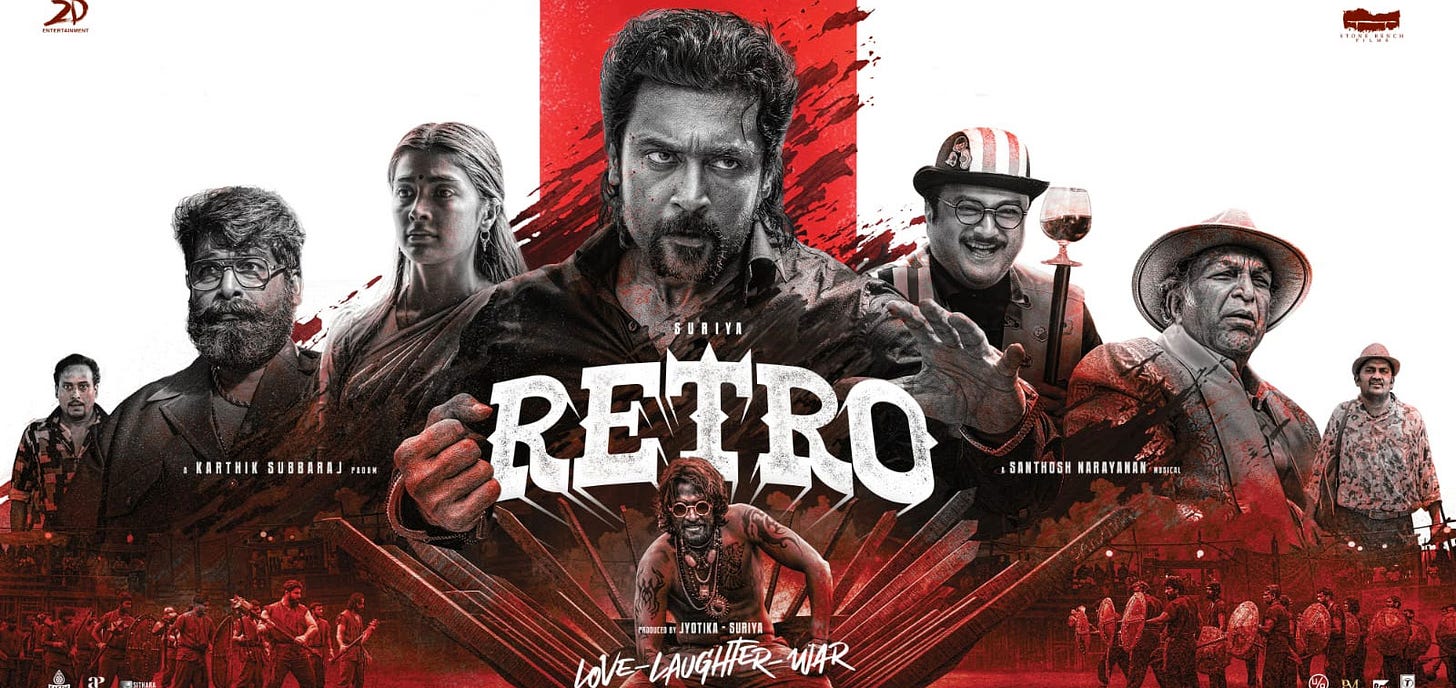

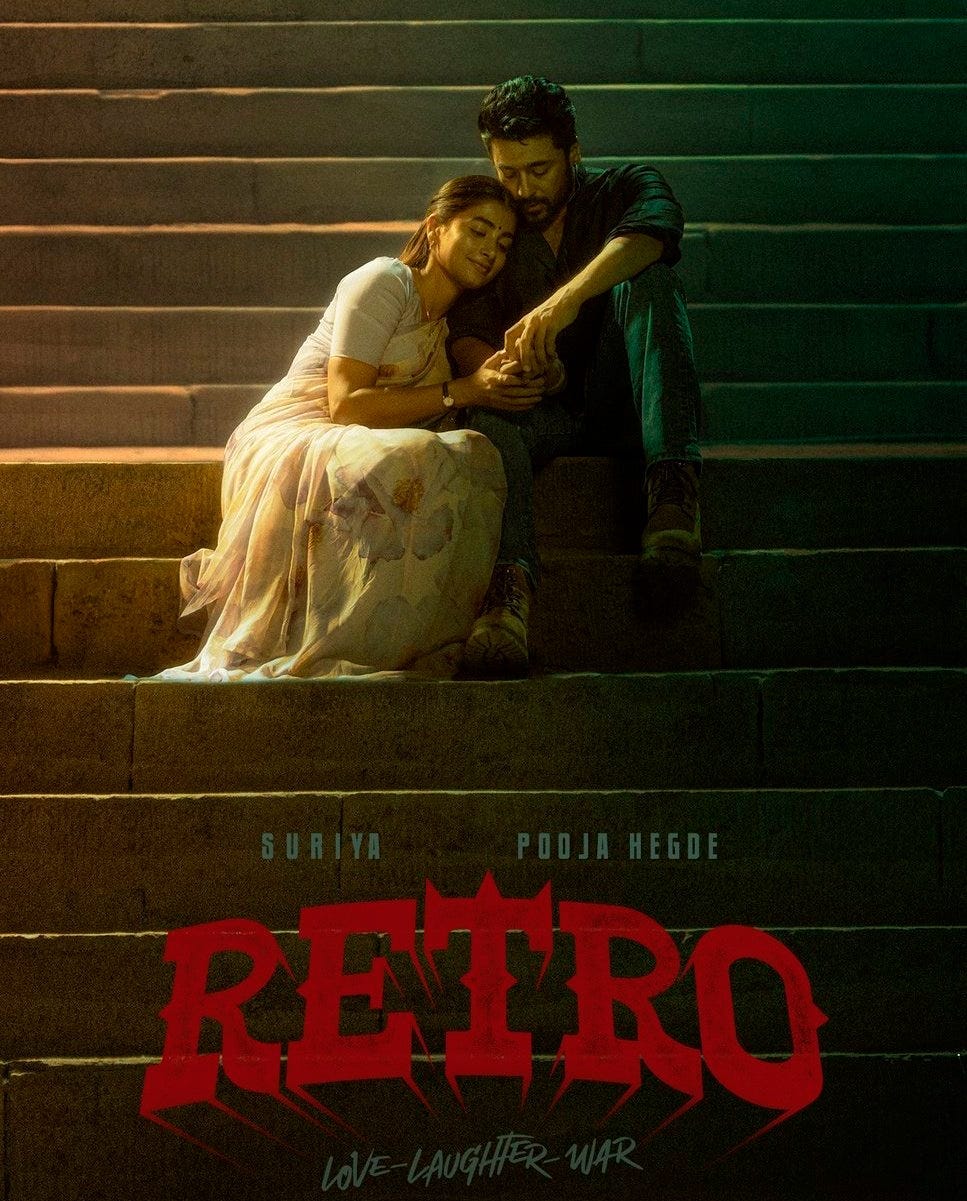

Retro is a thrillingly unpredictable gloss on the story of Lord Krishna, a gangland love story that shatters into a thousand other genres following a disastrous wedding party, captured in a tour-de-force 15-minute long take. Suriya stars as Paarivel (born on Krishna’s birthday) - who grows up as orphaned unsmiling muscle for burly gang leader Thilagan (Joju George). Thilagan raises Paari to be his personal enforcer when he discovers his gift for fisticuffs. But Paari swears off of violence to win the hand of the pacifistic Rukmini (also the name of Krishna’s first wife, played by Pooja Hegde).

This leads to the wedding, in which DP Shreyaas Krishna follows Suriya up and down the three-story building as he participates in a thrilling group dance, fights off dozens of thugs, and then chops Thaligan’s arm off in the middle of the dance floor - horrifying Rukmini and sending Paari off to jail (while Thilagan gets outfitted with a golden prosthetic arm that improves his bashing skills). It’s a beautifully staged sequence that is a pivot point in the narrative, upending Paarai’s path to enlightenment and transforming him into the “demon” he will soon be nicknamed.

Parrai’s time in prison is of course where he trains in martial arts, his fighting prowess so impressive he gets sold off to an underground fighting ring held in the back of a colonial rubber plantation. Founded by the English, it has been passed down to Indian owners who have similar repressive attitudes (and a gator pit). The father, Rajavel MIrasu (Nasser), demands to be called king while his son Michael (Vidhu) is the debauched prince urging teams of prisoners and employees to battle each other to the death with rubber weapons manufactured on site. And I haven’t even mentioned Dr. Chaplin (Jayaram) and his laughing cure, who spends the movie trying to get Paarivel and the beaten-down residents of the plantation town to crack a smile, an emotional outburst that could shake the foundations of their town. Kept under the Mirasu’s thumb like indentured servants in a horrible cycle of poverty, they are silent until holding rocket launchers on their shoulders like a group of rundown Rambos.

Reactions to Retro have been mixed at best. Hollywood Reporter India critic Anupama Chopra chastizes Subbaraj for including “too many things” in this wide-ranging interview, while Baradwaj Rangan bemoans that “the emotion gets lost amidst the action”. I would agree with Rangan if he was discussing Jigarthanda DoubleX, whose emotional appeals to the displacement of native tribes, while laudable, halts the forward momentum of the film and turns it into a lecture. Retro builds its entire edifice around Suriya’s face, waiting for him to crack a smile - and in turn triggering the villagers to guffaw. In this way he weaves Paari’s journeyr with that of the villagers, both straining to fight against the history of colonial and oligarchical repression. And instead of ending on the sound of bullets, it’s the echo of defiant laughter that closes Suriya’s fight against Thilagan and the Mirasus, a pacifist gesture that sanctifies the love of Paari and Rukmini. I think Retro is his finest work since the first Jigarthanda (2014), anchored by Suriya’s brutal and soulful performance.

Suriya made his film debut in 1997’s Nerrukku Ner, an action film produced by Mani Ratnam through his company Madras Talkies. It’s hard to find an Indian film artist who hasn’t been influenced by or worked with Ratnam, a restless experimenter who jumps from swooningly beautiful romantic dramas (Geethanjali) to chase films (Thiruda Thiruda), political thrillers (Roja, Bombay, Dil Se…) and grandly emotional melodramas (Kannathil Muthamittal). He has omst recently adapted the Tamil epic novel Ponniyin Selvan into a two-part blockbuster after decades of trying to adapt it for the screen (I went into detail on this for The Believer).

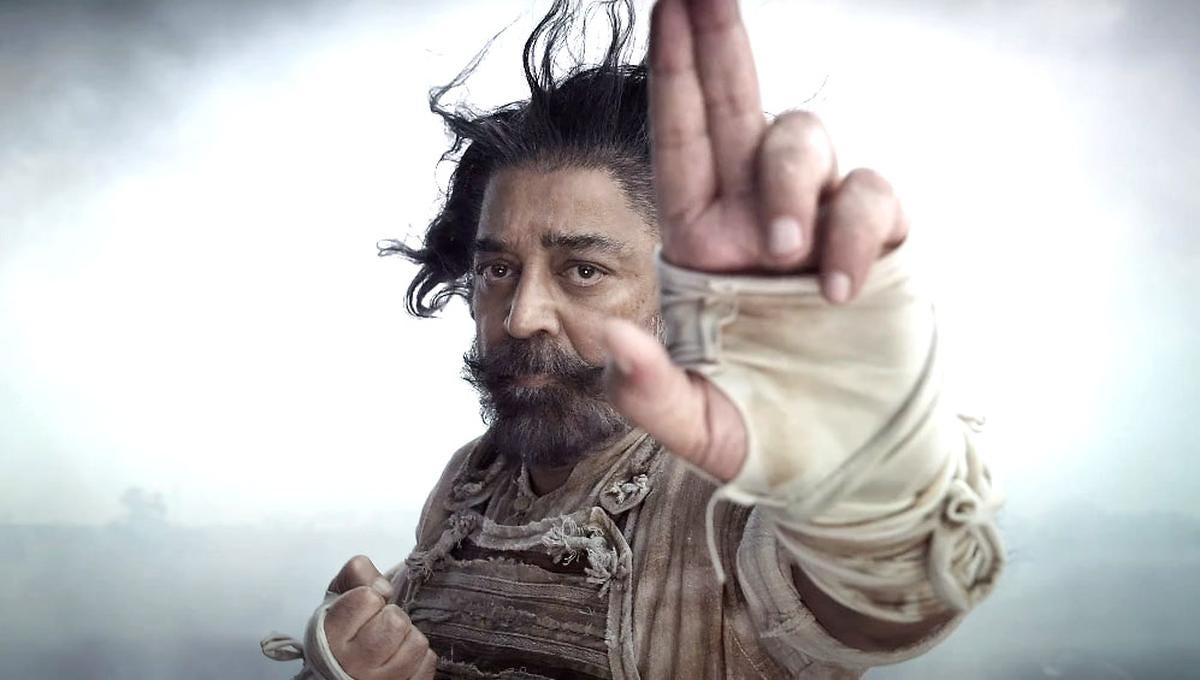

Kamal Haasan is one of the most enduring stars of Indian cinema, having started his career at the age of 6 in 1960 (in Kalathur Kannamma). He gives one of his most iconic performances in Nayakan, a soft-spoken interpretation of Bombay gangster Varadharajan Mudaliyar. Despite the film’s massive success, Haasan and director Mani Ratnam never worked together again until Thug Life, making it one of the more anticipated films of 2025. Nayakan is a novelistic drama of a mobster’s rise and fall, while Thug Life is more of a star-driven blockbuster set up to serve Kamal Haasan’s fanbase. The screenplay is credited to both Ratnam and Haasan, and follows Haasan’s mob boss Sakthi and his complicated relationship with his adopted son Amaran (played by Simbu - who was even more beloved by the 42nd Street crowd I saw it with than Haasan). Amaran’s dad was gunned down in a siege when the cops were trying to take down Sakthi’s gang, and loses his young sister in the crowd amidst the tumult. Sakthi promises to find his sister, no matter how long it takes, and takes Amaran in as his own. Amaran grows up to be Sakthi’s right hand man - and when Sakthi is imprisoned for a short spell, Amaran takes over the gang and grows the business, sewing doubts in both men’s minds about who is best suited to lead the gang moving forward.

This setup recalls Ratnam’s Thalapathi (1991), his only collaboration with Rajinikanth, in which a powerful gangster frees an orphan from jail and they grow to be like brothers. Similar to how Howard Hawks described A Girl in Every Port, it’s a love story between two men, and a deeply moving one. It makes sense that Ratnam would go back to the same well of ideas - Thalapathi is one of his many masterpieces - and it is fascinating to see Ratnam’s vision of melodrama adjust to the demands of modern Indian blockbusterdom. You can see all the beats coming, of Sakthi’s jealousy of Amaran’s ascendence, the inevitable betrayal and even more inevitable revenge. But they are all staged with such assurance, and set to A.R. Rahman’s nerve jangling score, that it is still a roaringly satisfying thriller. I was especially impressed with the opening siege, shot in B&W with a hail of police bullets dispersing a de-aged Haasan and his crew across a slum housing complex. This cursed place is the fulcrum that launches Amar out into the world and the same one that will crush him. Ratnam is expert at depicting the inescapable weight of memory - and the eternal return of this slum into Amar’s cortex, the image he can’t shake, will be his undoing.

Sure Trisha is cast in a thankless role as Sakthi’s young mistress, and some of the plot twists come out of nowhere, this is certainly a film with plenty of imperfections. But there are few filmmakers who can conjure transcendent emotional peaks out of pulp material like Ratnam, not since Frank Borzage anyway.