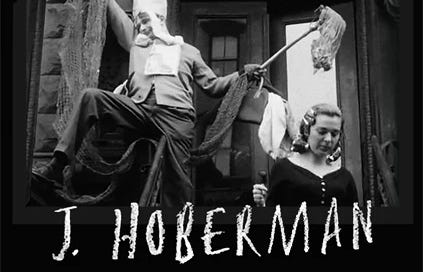

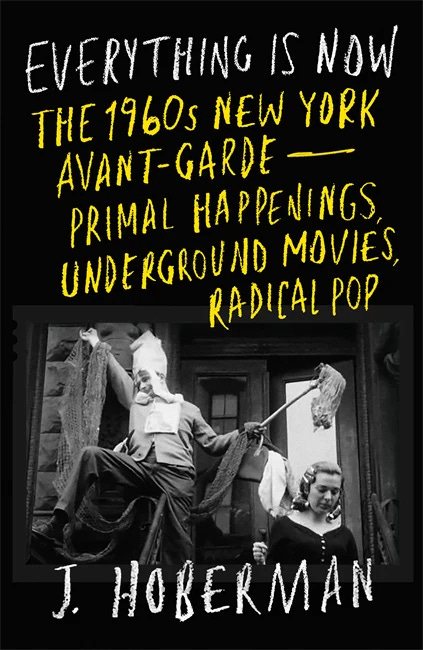

Everything is Now: An Interview with J. Hoberman

On underground movies, independent newspapers, free jazz and the New York Mets

J. Hoberman’s dazzling new book Everything is Now: The 1960s Avant-Garde—Primal Happenings, Underground Movies, Radical Pop is a kaleidoscopically detailed chronicle of experimental artmaking in 1960s NYC. It’s like reading the box score the day after a baseball game, but instead of Ks and HRs it counts the number of walkouts at Andy Warhol’s first screening of Empire (30 or 40) and enumerates the maladies inflicted on audiences by Tony Conrad’s The Flicker (headaches, eye strain, hallucinations, acute nausea). Hoberman marshals a mountain of research from underground newspapers and zines to recreate a present-tense bulletin of scene-making and breaking - shining a light not just on the art stars, but on all the broke-as-fuck painters, performance artists, playwrights, filmmakers, junkies, and hangers-on whose spirit pushed all those art forms into the future. It was a great pleasure to talk with Hoberman about the genesis of his book, the unknowability of Jack Smith, free jazz, and being disappointed in the New York Mets.

Hoberman curated an accompanying film series for Everything is Now at Anthology Film Archives that runs from June 20th to June 24th in NYC.

R. Emmet Sweeney: I'd like to start with something you mentioned at the book launch, that you've been thinking about this project for 50-plus years…

J. Hoberman: When I say I was thinking about it for 50-plus years, it was about dealing with the New York City that I emerged back into after graduating from Binghamton. And although I was involved in the here and now, I was fascinated by what had happened before.

RES: You describe Everything is Now as a memoir, not of your direct experience, but of this period of artistic ferment that you just missed. How did this period and these people loom so large in your teenage psyche?

JH: I certainly read about a lot of it. I started reading The Village Voice when I was in high school. They went to see underground movies…and I was aware of pop art. A lot of that I got from The Voice. And then a certain amount of hanging around. I used to go down to the West Village on weekends. So I knew that scene with the coffee houses and the music there too. And then when Ken Jacobs came to Binghamton, I went to a lot of stuff because of him, not just from his films, but from things he would say. He talked all the time about Jack Smith, and he brought up other filmmakers. So that was very important too.

By the time I was a senior in college, I was going down to the city a lot. My parents lived there, so I always had a place to stay. And so I started going to events. I appear in some form or another in every chapter, even if it’s only to report on my parents having gone to see The Connection (1961) in the first chapter.

RES: Your memory of going to the Jack Smith loft performance Withdrawal From Orchid Lagoon with Ken Jacobs and Jonas Mekas was really indelible. It sounds like Ken and Jack hadn’t seen each other for a while at that point…

JH: They probably had some run-ins during Ken's tenure at the Millennium Film Workshop, because he's still angry at Jack for acting badly. But yeah, that got him to the loft, and that was a very significant experience for me. I don't believe I had seen Flaming Creatures (1962) yet. I really only knew about Jack Smith from Scotch Tape (1959) and from hearsay. Oh, I had also seen No President (1967) at Max's Kansas City. And going to that loft at midnight was really a formative thing for me. You go up there, you watch him…everything that he did was performative. Also, I don't think I talk about it in the book, but the slideshows that he did were phenomenal. And that's what inspired me to write about Flaming Creatures for The Voice. Although I didn't immediately follow up on it. The Voice really was my first experience of being published.

RES: Do you remember what made the Jack Smith slideshows so memorable?

JH: A lot of them were made in his loft using the lagoon as a backdrop. And they were not so dissimilar from the images in The Beautiful Book (1962). But because they were color and because he was using… I think it was a standard 35 millimeter camera, they had a casual quality. They were delightful. He was doing what he always does, having people in costumes that he's designed, posed in front of exotic backgrounds, simultaneously exotic and sort of Arte Povera. I was just knocked out by that, and then he would play music, his records. And everything would skip, he would skid over them, all that stuff I thought was great.

If anything ever broke down, and this was true in the performance too, it just was part of the show. Now, I think that this would be possibly interpreting it to suit myself, but what difference does that make? In other words, I will never know what Jack Smith thought he was doing. I think Smith said that it's something that artists have, in his essay on Josef von Sternberg [Belated Appreciation of V.S. - collected in Wait For Me at the Bottom of the Pool: The Writings of Jack Smith, ed. J. Hoberman and Edward Leffingwell]. He says something like, artists have explanations for why they do what they do, but that's all it is, their explanation.

RES: Some of the most valuable things about the book are your descriptions of these live happenings and performances, most of which were not preserved in any way. You bring them back to life.

JH: Well, thanks to the underground press, I must say. That's the single most important record of all these things because video didn't really become commonplace until the early ‘70s. And there is a video recording of one of Jack's performances. It doesn't really do it justice, it's just a relic of the period. Some video makers wanted to document him. He fights with them, it breaks down. So I guess it's valuable for that.

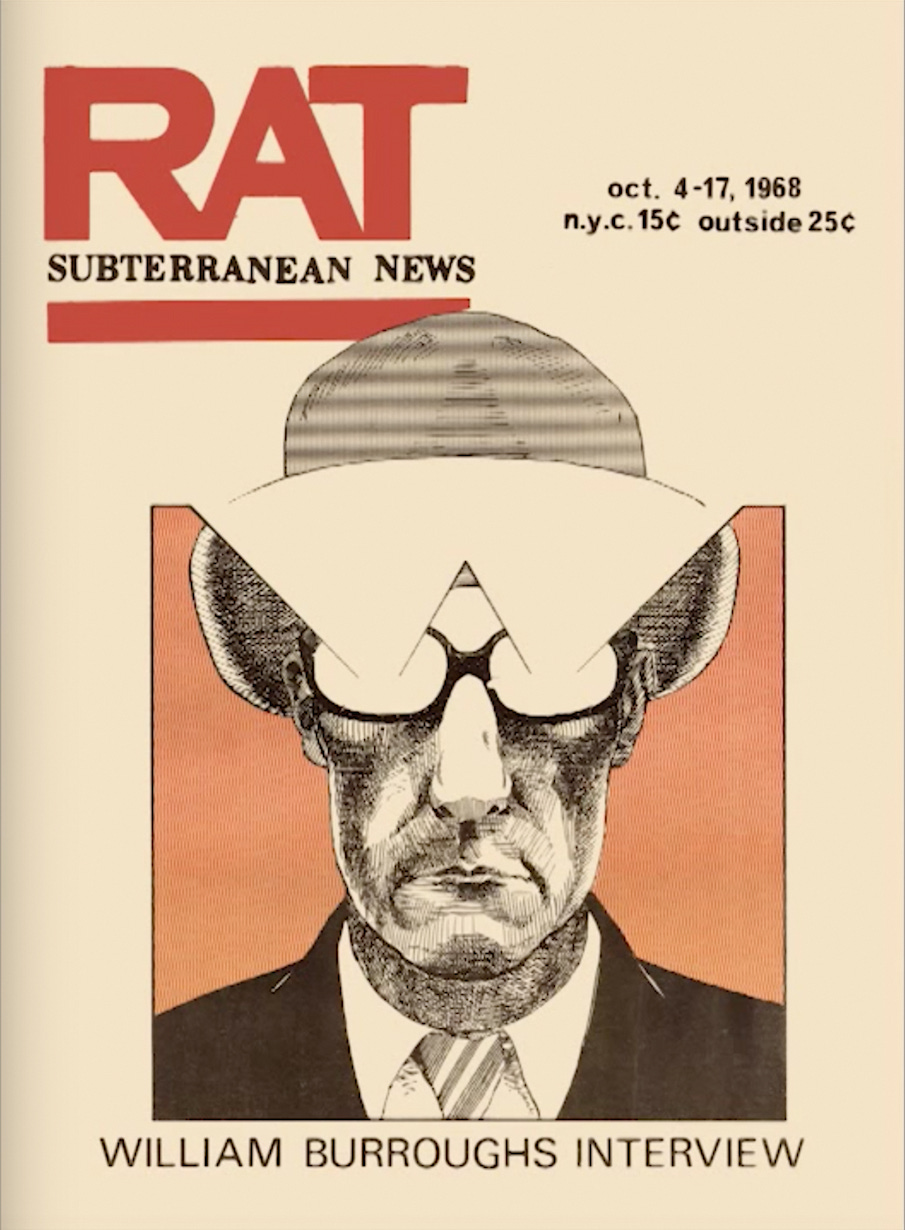

RES: And you mentioned the underground press. One newspaper I had never heard of before was Rat, which you quote a lot in the second half of the book, and whose history is as fascinating as the artists they are covering. They're involved in terrorist bombings, a feminist takeover of the paper…were you reading that at the time?

JH: I was a casual reader of EVO (East Village Other) and Rat. By the time I moved back to New York the Rat was exclusively political and I wasn't that interested in it. EVO, I thought of it being indifferently written. I've since revised my impressions. It's just what I thought then, that the writing was much better in The Voice, but that EVO knew more about what was going on. And I love the cartoons in EVO, that was my favorite aspect of it.

I didn't know about the feminist takeover of Rat, an incredible story. Nor do I even have a clear memory of those bombings that Jane Alpert was involved in. And of course, what I remember is the ‘69 World Series, but I was up in Binghamton for that year, so I guess I was not really thinking about the city. One of the things that's interesting about the period is that at the same time that the scene is relatively small, particularly in the first half of the book, people are still somewhat siloed, although I was always most interested in the interstitial stuff, which we're focusing on in the Anthology Film Archives program.

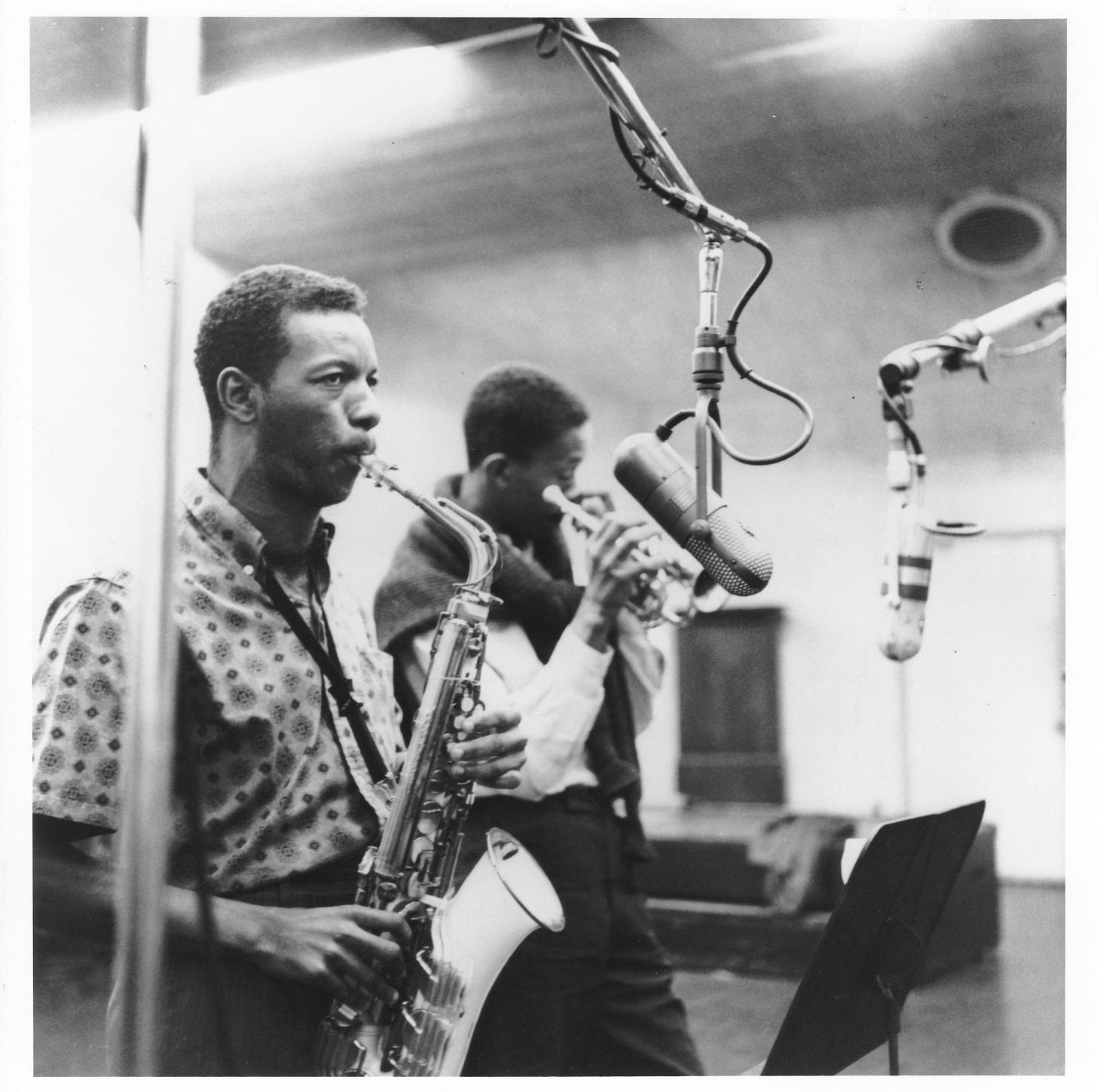

RES: I also love how you weave in the story of Ornette Coleman and Free Jazz and their contact points with the experimental art scene. And Sun Ra keeps reemerging throughout the book as well as this phantom force.

JH: I knew about free jazz in the late ‘60s because that's when there was this concerted effort among the rock critics. I got very interested in Pharoah Sanders, Albert Ayler, and Don Cherry. So I was buying those LPs rather than buying rock LPs. And there were all these concerts in Central Park, Mayor John Lindsay really deserves credit for this. As a way to keep kids happy, it would be in Central Park for a dollar. So I heard Ike and Tina Turner, and I heard jazz there too. By the late ‘60s, that became at least as interesting to me as rock music, except for Jimi Hendrix and Sly and the Family Stone. Black nationalism was a counterculture. Black counterculture that developed on its own. And if anything, you could say that it was a model for the other counterculture, although people might not have perceived it that way.

RS: Yeah, that comes out as you track Leroi Jones/Amiri Baraka’s career, his extraordinary writing and your description of the Slave Ship performance, with performers puking in critics’ laps, is so intense...

JH: I had never heard of Slave Ship until I began working on this book. That's true of any number of things, but it’s amazing that this seemed to have left no trace. And it's not as if it wasn't written about.

RES: Yeah I only know of him because of his writing on jazz, like Blues People, but had no idea about his theatrical career.

JH: And he was a very good poet too. When he was associated with the Beats, those poems are very good.

RES: Have you tracked the resurgence in Pharoah Sanders fandom? After that album with Floating Points the kids like him again.

JH: Well, great. I mean, I'm not surprised…he invented this whole thing, which I can't remember if it's spiritual jazz or something.

RES: Yes, spiritual jazz. And Alice Coltrane is now back huge as well.

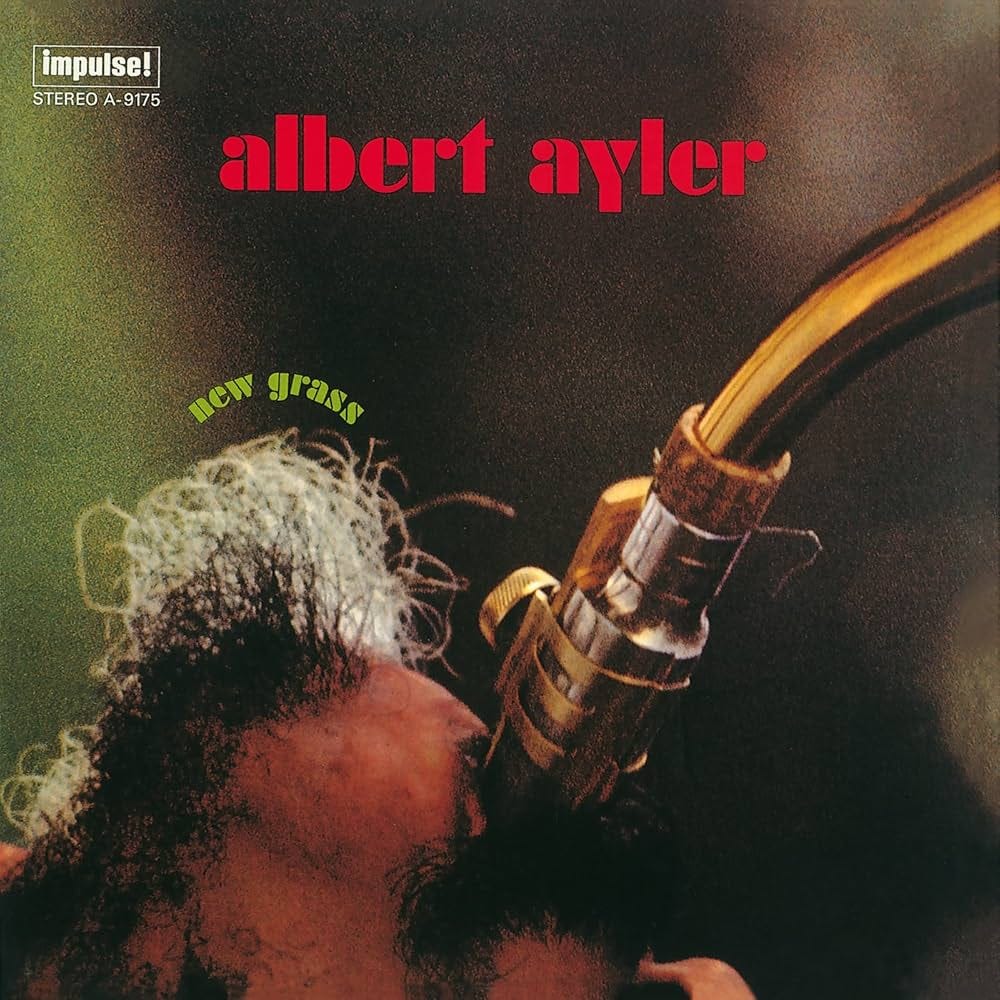

JH: What goes around comes around. It was really of a piece with what white kids were into. To some degree it was an integrated scene, but not that much. The Albert Ayler album, New Grass (1968), I loved that album. I used to play that album all the time.

RES: I never got into that one. I loved Live in Greenwich Village.

JH: If you read The Cricket or see what I quoted, they hated it! The black jazz intellectuals hated that. And they probably would have hated the Ornette Coleman album that came out, Friends and Neighbors…I had that one also. But Albert Ayler, he was my favorite. He's great! All his stuff is great! Well, actually, the one that he made after that is not…

RES: Music is the Healing Force of the Universe (1970) was too hippie for you?

JH: Yeah, and the singer is limited. I loved what he had on New Grass, the Soul Singers or whatever the hell it was, his gospel backup singers. But the other one was pretentious. And Leon Thomas was very big then too, after his Pharoah Sanders records. He put out some solo records, which I think Pharoah Sanders plays on. It was very important to me to have that in there and not to shut it out. It was also kind of a leap because I never really wrote about music. I knew about the musicians. What was hard for me was to describe the music. So I work around that. Reception, context. I mean, I certainly could recognize certain things.

RES: You do go into some detail about Dylan, who's a continually mutating figure in the book. Were you a Dylan guy?

JH: I certainly was at the time. But by the time of Self Portrait (1970) I got off the bus. I do like Blood on the Tracks (1975), but no, I got off the bus, although I'm glad he won the Nobel Prize. Dylan is one of those people, if he had been killed in that motorcycle accident, it would have been a stunning thing, like Keats or Rimbaud. But yeah Dylan and Warhol are the two big stars of this period, but I really did not want them to overshadow all the other stuff that was going on.

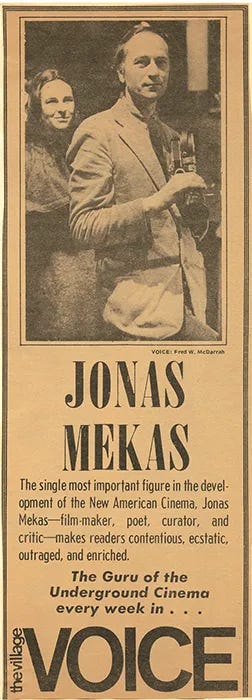

RES: You also mentioned at the book launch how you think the person that's mentioned the most in the book is Jonas Mekas. What was his influence and importance over that period?

JH: I realized when working on the index that he had way more entries than even Dylan or Warhol or anybody. I quote him a lot and I cite him a lot. There are really only two of his movies that I talk about in any length [Guns of the Trees and The Brig]. And they're kind of the movies which are regarded as uncharacteristic now. But his significance as an organizer and as a chronicler is enormous. And he also knew about more than film, although basically that's what he stuck to. He was around for other events. And I certainly read him in The Voice. To a large degree he was the person that I read the most.

RES: How did you decide what to include and exclude from the book from all of the activity and art that was being produced?

JH: Well, that's hard. First of all, there were certain things that I just knew more about. And then there were some things that I just couldn't find a way to put them in. Off the top of my head is Rosalyn Drexler, an interesting artist from the period. She was her own version of Pop Art, she wrote, she was a professional wrestler, she had plays. She was a real downtown character. And I mentioned her in passing but I could not find a hook to bring her in. And there are other people like her. There's another artist, Judith Bernstein, who’s still around. She was unexhibitable. Not only unsellable, she also couldn't get a gallery to show these…she was a bit like Barbara Kruger…they were placards with obscene graffiti on it. I didn’t get to see her work until recently. I couldn't find a place to put her in because she should have been there with Boris Lurie even though she didn't belong to that gang. And I wouldn't have imagined that Yayoi Kusama would have been as present as she is. At the time I thought she was a publicity seeker. I had no knowledge of her earlier work as a painter.

One of the reasons why I was inclusive was not just to mention more famous people, but to mention people who turn up who never become successful, in conventional terms of success. But they add a lot of texture to what was going on. There's a star system that develops, a very ‘60s thing. When people became art stars. But there were also people who had ideas and contributed and got sidelined or never emerged into the limelight.

RES: One of the major reasons this book exists are the underground, independent newspapers, which is not something that exists right now. Do you read film criticism anymore?

JH: What I used to read most closely was Cinema Scope. I get Cineaste, so I look at things there, but I don't really look for stuff online. I probably miss a tremendous amount of what's going on. I know a lot of people write for Screen Slate.

RES: Yeah, that's one of the few places left that accepts off the wall ideas…

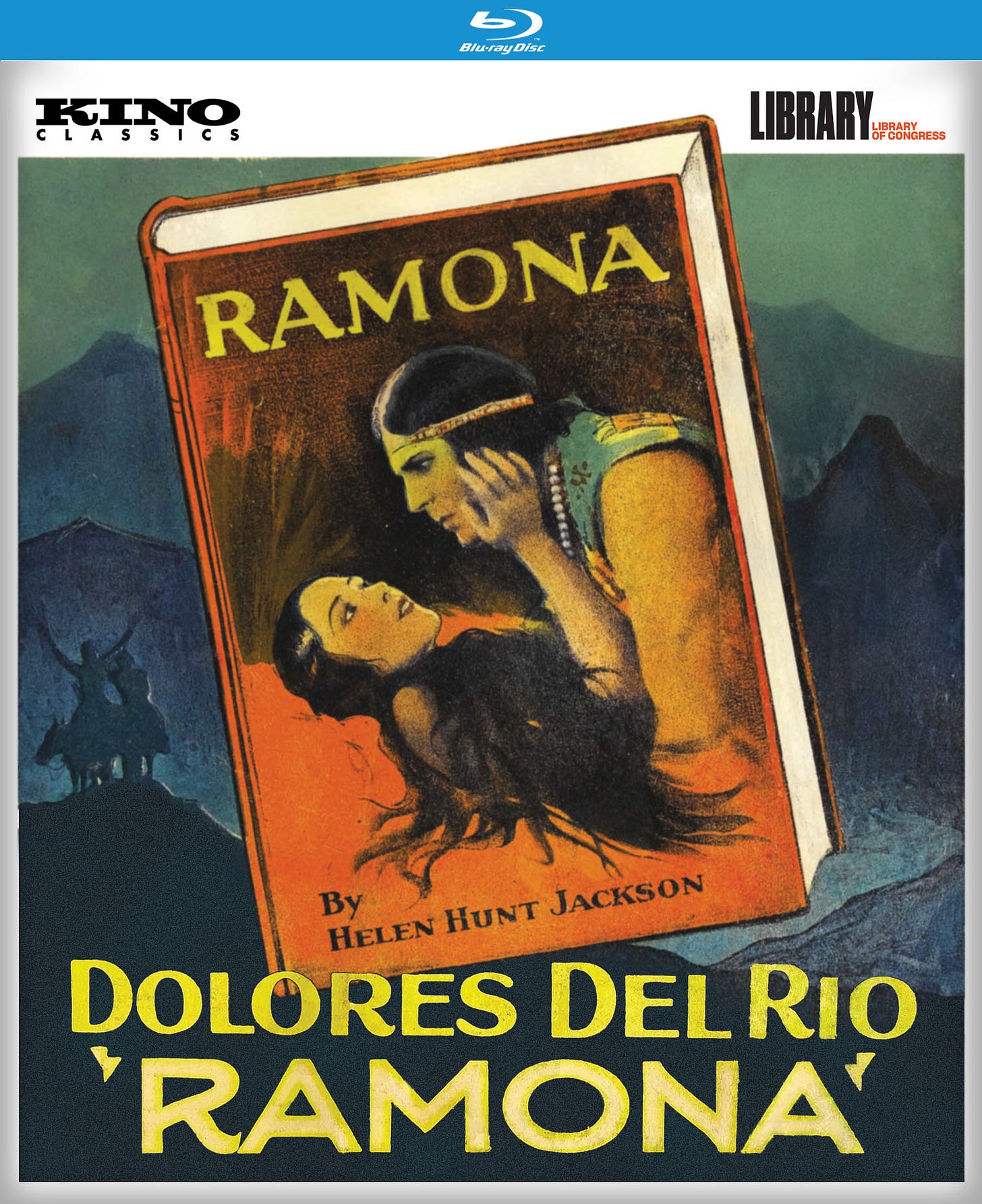

JH: Maybe I should be looking at that. In terms of other stuff, I get too many magazines and end up not reading them. I have a whole wall of DVDs, a lot of them from Kino Lorber, of course. Many from when I was reviewing DVDs for the Times. There's a part of me that wants to catch up on all this stuff. I'll give you an example.

I was curious to see Ramona (1928). My dad grew up with silent movies, and his favorite actress was Dolores del Rio. He was probably a teenager when this came out. The movie turned out to be such a woke movie! The director Edwin Carewe was half-Native American, part Chickasaw. After Ramona he made an anti-fascist movie, Are We Civilized (1934), which is not very good. But it’s amazing that it exists. Why isn't this guy better known? I looked in Kevin Brownlow's book. He's not mentioned. He made a bunch of movies and he had a perspective…

RES: I can’t go without talking about the Mets. I went to a Cyclones game on Father’s Day for Sean Manaea’s rehab start and he got bombed…they are getting thin in the rotation.

JH: I went to the Mets game with my grandson and my daughter…worst game of the season.

RES: You stayed to the end?

JH: Oh yeah [laughs]. There’s always something to watch. What a nightmare series! My theory is that the loss of Senga…they’ve all gone into a trance now. Canning isn’t a starter, he should be a middle reliever.

RES: Their pitching depth is really getting exposed. They need Montas and Manaea but their rehab has not been going well.

JH: And they were really feeling full of themselves! “The best team in baseball”. No. And CitiField is so in your face, I feel like such a fogey. But it’s a better built stadium than Shea. Shea was kind of a monstrosity. Of course the first two years I would go to the Polo Grounds. That was overbuilt, you felt like you were on a stoop. Pillars, iron girders. The bleachers had no protection from the sun. Before the Mets only one home run had been hit into the bleachers. There were very short foul lines. That Bobby Thomson home run would have been a pop-up in some other fields. A crazy stadium…my dad sold peanuts there when he was a student.

RES: Amazing. I love going to the Cyclones stadium in Coney Island, you can see the rides over the outfield wall.

JH: And you can walk down to Brighton afterwards. You know that every few years there's a Marx Brothers Festival in Coney Island? I got to talk about Duck Soup in the Coney Island Museum. It was priceless. And you know, my grandfather was the lawyer for the freak show. An abogado, a storefront lawyer. That’s what he was. Jews couldn’t be in law firms. He had an Italian partner and they had an office in Coney Island. I think the Turkish Baths was his main thing because that was always defending lawsuits. My mother and my uncle used to go to the freak show all the time, but it was so funny because my grandfather was such a straight arrow! [laughs].