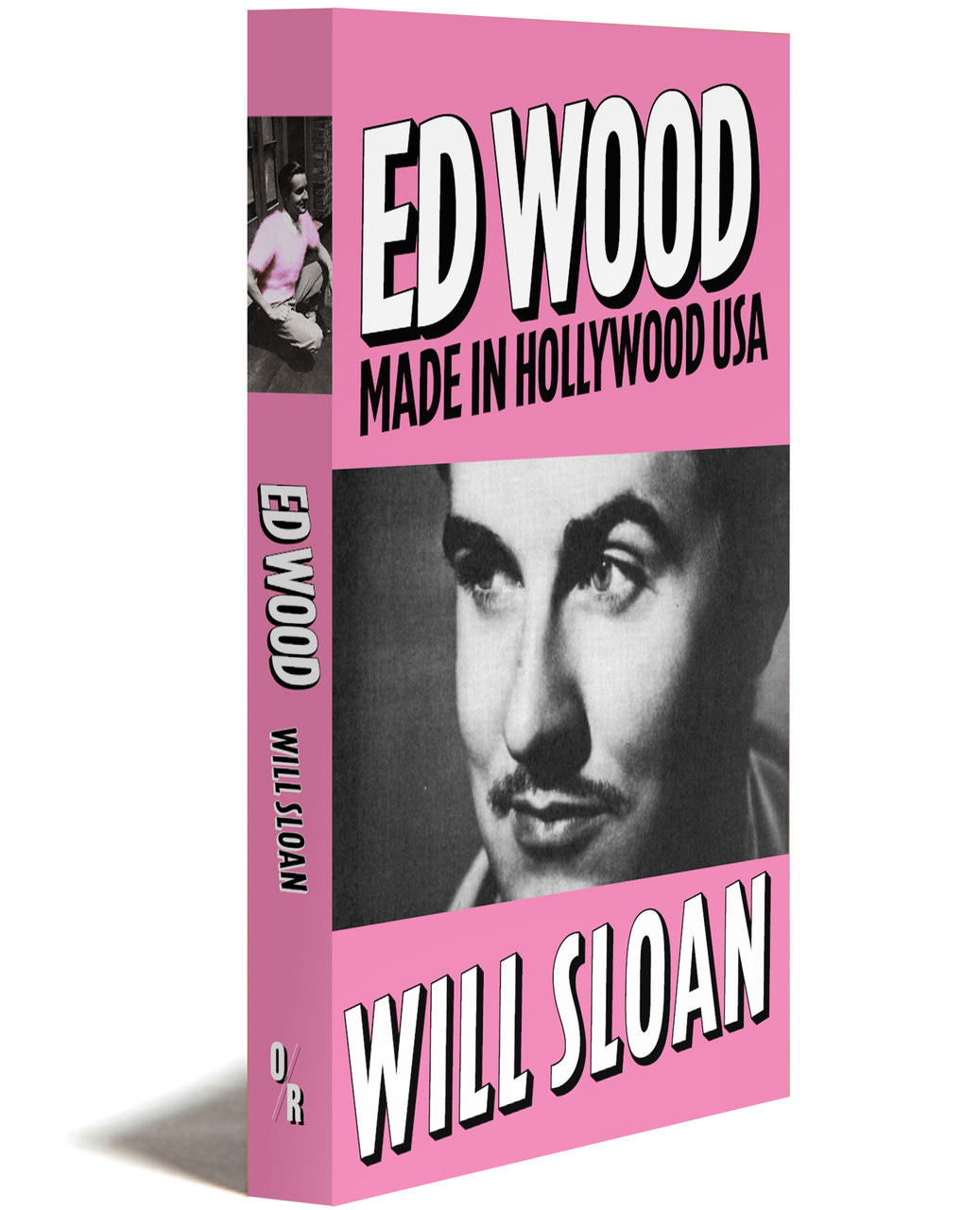

Against the Grain: An Interview with Will Sloan about Ed Wood

Will revalues the "worst director of all time"

The legacy and infamy of Ed Wood was cemented upon being called “the worst director of all time” in The Golden Turkey Awards (1980) by Harry and Michael Medved. What Will Sloan proposes in his deeply researched and lucidly argued new book Ed Wood: Made in Hollywood USA is….maybe he wasn’t? A Wood-ologist since childhood, he makes no claim for the director’s technical mastery, but wants to shift focus to the obsessive weirdness of his work, an artist who truly channeled his inner turmoil onto the screen. I spoke with Will about his lifelong journey of Wood appreciation, the complex reality of Wood’s sexuality, and getting beyond definitions of good and bad.

R. Emmet Sweeney: I just saw that you are bringing a 16mm print of Plan 9 from Outer Space (1957) to screen at Metrograph on October 9th in NYC. When did you acquire it?

Will Sloan: Yeah, the print is in transit right now. It should be arriving at Metrograph today because they have to check it. They have to make sure it’s playable. I hope to God it’s playable. The eBay seller told me it was playable. So we’ll find out. I’m very excited.

RES: So you haven’t run it before.

WS: I haven’t run this print before. So this is quite dangerous what we’re doing. But I have a good feeling about it. I got this print on eBay, and I have to assume it’s probably a TV print, which is how Ed Wood’s work would have circulated for a very long time. Some 35mm prints were made of Plan 9. It had a theatrical run in 1959, 1960, but it really built its audience on television. So I feel like we’ll be getting a fairly authentic experience of how the movie was seen by the first audience that embraced it.

RES: So it was probably cut for television then?

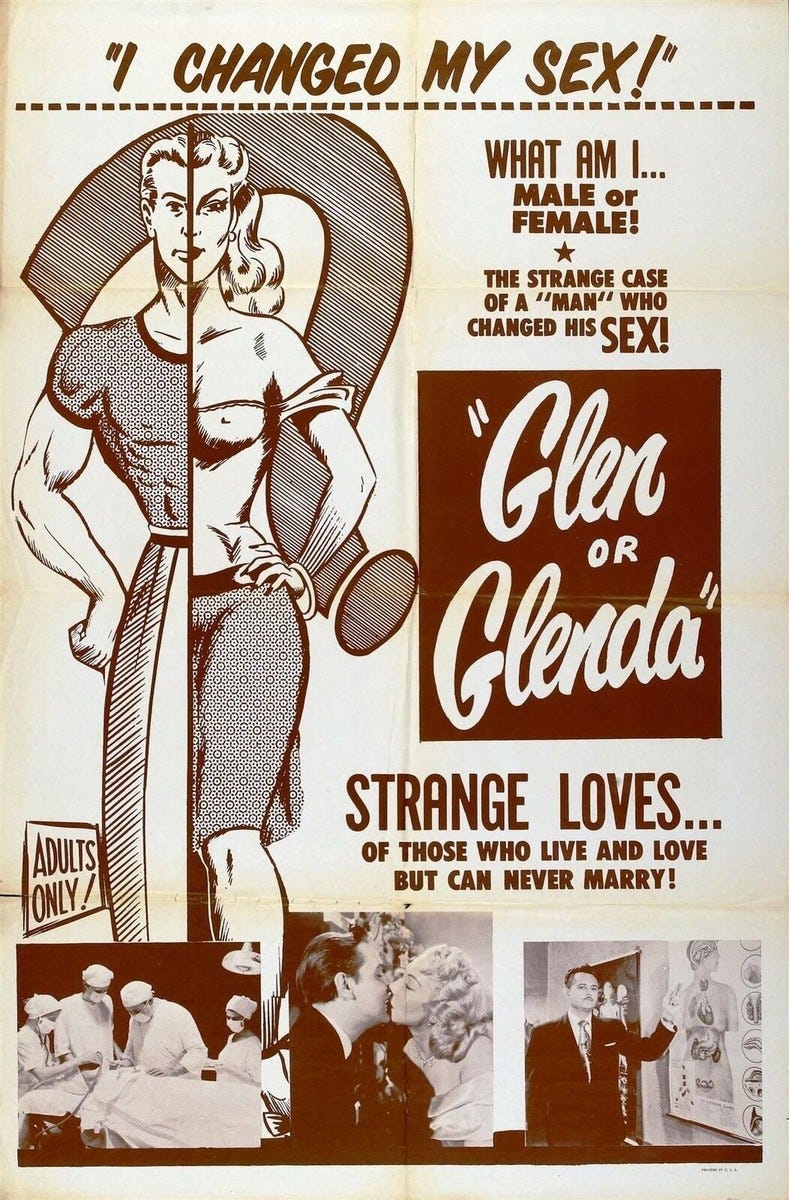

WS: I’m very excited to see, frankly. Something I like about Ed Wood’s movies, especially Glen or Glenda (1953), is how it exists in so many different versions. You watch the DVD here, or the AGFA scan there, or a 16mm print, a VHS copy. They’ve all got some scenes that aren’t in other versions. And so his movies feel like having the same dream over and over again, but with slight variations.

RES: Have you gone through different phases of Ed Wood appreciation?

WS: Well, the first time I saw Plan 9 from Outer Space, I was maybe seven years old and I had been told that it was the worst movie of all time. So I went in very primed to laugh at it. And there are certain things in that movie that even a seven-year-old can see are deficient, like the flying saucers on the strings, the cardboard tombstones falling over. When the situation with Bela Lugosi and his double, played by Tom Mason, was explained to me, that was pretty obvious. When you’re seven years old, you don’t have a lot of power. I liked pretty much every movie I saw when I was seven. You don’t have a lot of power and you don’t have a lot of taste. And so it felt nice to be able to flex some critical muscles. It felt nice to feel superior to something that an adult had made.

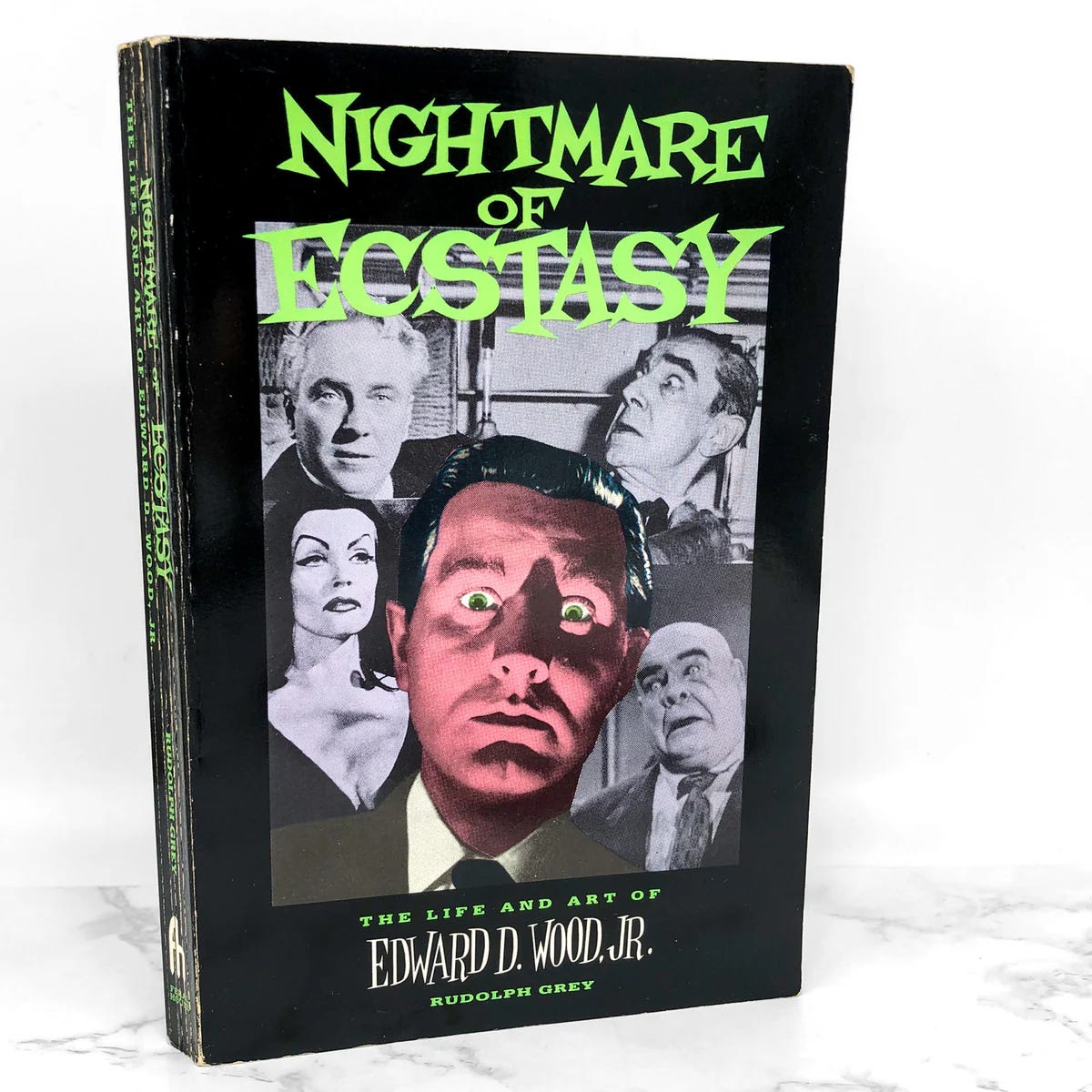

But definitely Plan 9 from Outer Space stuck with me. I saw it a few times. There was a documentary that I saw when I was maybe 11 or 12 called Flying Saucers Over Hollywood, The Plan 9 Companion, which was made for video in the early ‘90s. Around the time of Rudolph Grey’s biography, Nightmare of Ecstasy, and a little bit before the Tim Burton film. That was really fascinating to me, just learning about his entourage, everybody connected to him seemed to have a strange story. Vampira, Tor Johnson, Criswell, Paul Marco, Bunny Breckenridge, all these people were colorful Los Angeles characters in their own right. And then learning about Ed Wood’s own story. I read Nightmare of Ecstasy when I was a teenager…I’ve read that book backwards and forwards over and over again. It’s such a fascinating, tragic story of this man on the fringes of Hollywood with these really deep, painful feelings he was clumsily expressing in his art, then destroyed by his addiction. All of that gave me a new empathy for him.

RES: He had this compulsion to make movies. He was going to one way or another. It clearly wasn’t helping him economically.

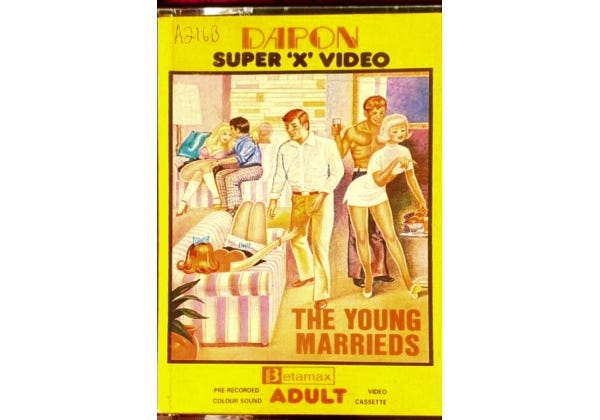

WS: I think what gets me about Ed Wood on that note is, people who invested money in his movies called him a con man, but he was only a con man for art. He himself never made a dime off these movies. If you read letters that he wrote that have been printed in various sources all through his life, he remained delusionally optimistic about making movies to the last year he was alive. In the last days of his life when he’d just been evicted from his home he was still talking about making a Bela Lugosi biopic. When he had the opportunity to direct those porn movies in the ‘70s he was very happy and excited to do it because he’s a director on a set. How can you not like that guy? One of the things I wanted to do with the book was work through the feeling of, OK, in many ways, he’s not talented. But also, I like this guy. And I like the ideas. I like the point of view in his movies. And so it’s reconciling those two things.

RES: He doesn’t have that technical training, so you get a different vision of what a film can be and what could be put on screen. He puts you in a completely different space than you’re used to. That kind of disorientation can be fun.

WS: The boy from Poughkeepsie, New York, who grew up dreaming of Hollywood. And then when he got there, wanted to make Bela Lugosi horror movies and Poverty Row Westerns as these things were getting firmly out of fashion. I like that guy. And I like the guy who is wrestling with these feelings that I don’t think he even fully knew how to articulate in a movie like Glen or Glenda or later on, frankly, in a movie like The Young Marrieds (1972), which is also a very personal film. I like the artistic spirit of a guy like that.

RES: He must have had some kind of charisma to get these movies made. In your research what did you learn about his personality?

WS: Well, to his charisma, I think he was a very well-liked guy, which doesn’t mean he was necessarily taken seriously. Sam Arkoff, the head of American International Pictures, said in an interview that, “frankly, in my book, Ed Wood was a loser”. And a lot of people who had power regarded him as this flighty, eccentric figure who they didn’t take seriously. But everyone liked him. Gregory Walcott, who starred in Plan 9 from Outer Space, and quite resented Ed Wood for how he took a lot of money from the Baptist Church of Beverly Hills. He said things like, “you couldn’t not like Ed Wood.”

RES: So many artists from his era have made films that have been forgotten. They’re in the dustbin, but his films continue to endure and grow in fandom.

WS: Yeah, and I think that speaks to his personality, his artistic personality. Because if it was just about the flying saucers on strings and the cardboard tombstones falling over, I think the movies would be a momentary novelty. Even when the Medveds were writing about him for the Golden Turkey Awards, I think they understood that there was something about his artistic personality that was very strong compared to other directors.

RES: Is that what separates him from other so-called “bad” filmmakers?

WS: I think so.

RES: And you do consider him a bad filmmaker?

WS: Yeah, that’s a complicated question. And I think the thesis I came to is that he’s not merely bad. I’m interested in Ed Wood because he’s not fully reclaimable. You look at a movie like Final Curtain. I don’t know if you’ve seen that one, but it was a 22-minute TV pilot that he made in the vein of The Twilight Zone. And it’s about an actor who’s in an empty theater late at night after the show is over. And there’s this very ripe narration of this actor’s thoughts. And he’s looking around this empty space, and the narrator is going, “What was that sound? Is it a ghost? Could it be a ghost? Or is it merely the sound of my heartbeat?” Over and over again. It’s Ed Wood trying to do a Val Lewton horror movie. The shadows are scarier than a monster kind of thing. But he doesn’t know how to use editing and lighting to generate tension and suspense. There are basic fundamentals that he didn’t master. So on that level, I think Final Curtain is a bad movie. But I like the chutzpah of making this movie with nothing and saying, “I’m going to show you an empty room and I’m going to have this narrator insist that it’s really scary. And you’re going to sit here and I’m going to beat you into submission into thinking that it’s scary”. And he fails, but I find the instincts of a guy who would try to do that very charming.

RES: Is that something that aired, or was rediscovered in a closet somewhere?

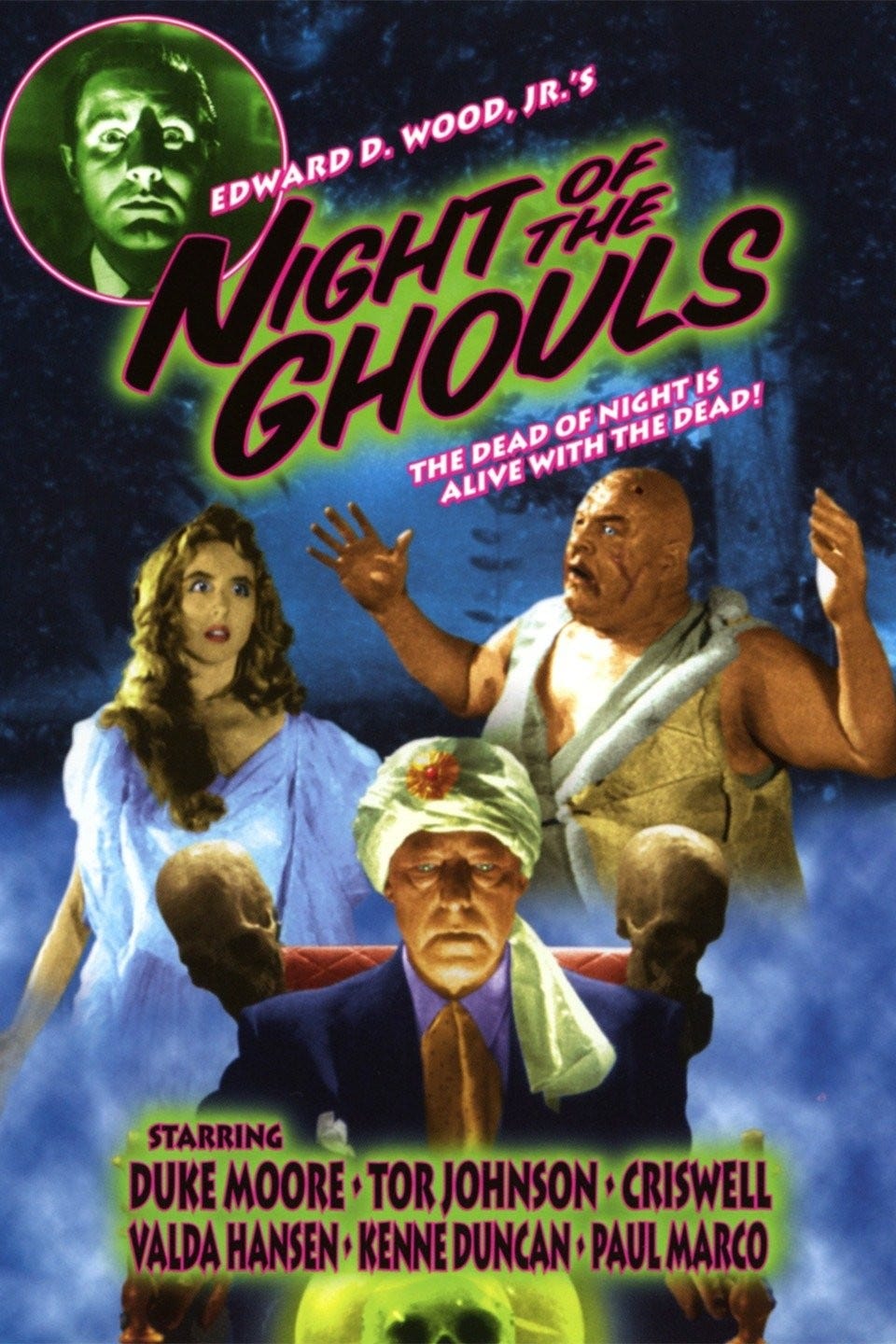

WS: Yeah, it was rediscovered about 10 years ago. It had a premiere in 2012 at the Slamdance Film Festival. It was lost, it was in the hands of a private collector for many years. But a lot of that footage was incorporated into Ed Wood’s later film, Night of the Ghouls (1958).

RES: As you’ve been going through this whole research process I’m sure you’ve talked to a lot of Ed Wood collectors, scholars, monomaniacs. Have you felt embraced by that community?

WS: Well, I have felt a part of that community for a long time. There’s a great Facebook group that’s run by a guy named Bob Blackburn, who is the heir to the Ed Wood estate. He was Cathy Wood’s consigliere to the outside world in her later years. She left whatever she had in her will to him. And he’s done incredible work editing anthologies of Ed Wood’s writings, including Blood Splatters Quickly and Angora Fever, the Collected Short Stories of Edward D. Wood, Jr. So he’s done incredible work shining a light on parts of Edward’s legacy. But he has a Facebook group where everyone in the Edward world is there sharing news and links and that sort of thing. So I definitely feel part of that world. I think the book has been warmly embraced by people who know Ed Wood. I’m probably not telling them a lot of things they don’t know already. But what I’m trying to do is synthesize 30 years of Ed Wood scholarship, because there’s been a lot that’s happened in the world of Ed Wood since the Tim Burton movie came out. So I’m trying to bring it all together into a package that can tell the outside world the good news about some of the discoveries that have been made about Ed Wood since.

RES: Yeah, I hadn’t known about Final Curtain or the pulp novels he was writing. Has there been a full biography of him?

WS: Well, the quintessential Ed Wood book, the main gospel of Ed Wood studies is Rudolph Grey’s book, Nightmare of Ecstasy, The Life and Art of Edward D. Wood Jr., which was published in the early ‘90s. It’s the credited source for the Tim Burton film, and it’s an oral history. Rudolph Grey, the author, spent much of the 1980s going around interviewing everybody who knew Ed Wood and presented their recollections in oral history style. And it’s a fascinating book. It’s full of incredible stories. It’s also a little hazy. People contradict each other. Certain people are more reliable than others. So it’s a little Rashomon-like at times. The book is proudly not rigorous. Bit it’s a very evocative book and it’s the bedrock of all Ed Wood studies. There is a guy named James Pontolillo who’s done two incredible books that aren’t really biographies, but they’re deep dives into specific moments in Ed Wood’s life. There’s one called The Unknown War of Edward D. Wood Jr., which is about his wartime years. And there’s another one that he’s just done called The Muddled Years of Edward D. Wood Jr., 1946 to 1948, where he’s done some really serious work going into the archives, looking at newspaper records, looking at Edward’s publicly available war records, and correcting the record about a lot of assumptions and myths about his life in that period. Edward’s life is a little hazy at times. It’s not like people were reporting on him at the time. He wasn’t Orson Welles or Alfred Hitchcock, where there’s a vast body of contemporary interviews and reportage about his every move. So a full, really rigorous biography would be a challenge.

RES: So Ed Wood exaggerated his war record?

WS: That’s right. I mean, we have James Pontolillo to thank for that because through all these years of people reciting these war stories that Edward told himself, James was the first guy to actually think, “Hey, maybe we should look at his war records and see what he actually did”. So for example, Ed Wood claimed for many years that he fought at the Battle of Tarawa, which is only half true. He was in the second wave, he was part of the cleanup crew. I guess he didn’t think it was a good enough story. He claimed for years that his front teeth were knocked out by a Japanese bayonet who he righteously killed in fury and revenge. It wasn’t that. It was a much more mundane reason that he lost his front teeth. One of the most treasured bits of Edward lore is that he supposedly wore women’s underwear under his uniform while he was fighting the Battle of Tarawa. He would say to his friends, “I would rather have been killed than wounded because if I had been discovered wearing women’s underwear, that would have been a real problem for me”. If you use common sense, he was in close quarters with a lot of men. They were changing in close quarters. They were sleeping in close quarters. He would have been discovered wearing women’s underwear.

There’s a bit in Glen or Glenda, the whole story of Anne the transgender woman, where it’s talking about her wartime experiences and how in every town that she visited she had a suitcase waiting for her at a locker where she’d stashed away women’s clothing. And I feel like that’s probably what Ed Wood actually did. He’s probably indulging in cross-dressing in his off hours.

RES: His films seem to be outlets to work through questions about his own sexuality and gender identity. He always claimed he was heterosexual…do you take him at his word?

EW: It’s an unanswerable question. He always maintained that he was heterosexual. And he certainly had heterosexual appetites. There’s a lot of writing that he did, he wrote a lot of nonfiction articles about drag and cross-dressing. He wrote a lot of novels about drag themes. He seems to have repeatedly identified himself during his lifetime as a cisgender heterosexual man who wore women’s clothing. That seemed to be an important identity to him. How would he have identified today? I don’t know. I mean, he certainly had more access to information about gender diversity than the average man of his time would have. At the same time, he had a drag persona named Shirley. And when he was Shirley, he was Shirley. In his novels he is very obsessed with the idea of passing. He’s very interested in gay sex, frankly. There are lots of scenes of anal penetration in his novels.

Ultimately, I think it’s an unanswerable question. It’s very possible that if he were alive today, he might have identified similar to how Suzy Eddie Izzard identifies. She talks about being in girl mode, boy mode. Maybe that’s where he would have been now. But what I will say is I think you see some evolution in his attitudes or his relationship with his own sexuality as his life and career progress. In Glen or Glenda, he’s very anxious. It’s all about coming out in the 1950s. He’s very eager to enforce certain binaries of gay and straight, male and female in that film. When the Anne character in that film undergoes surgery, it’s very important that she become a woman. That she would play the role that society would expect of her as a woman. But by the 1970s, it seems that Edward himself was much more open about being a cross-dresser. He would show up at the office at Pendulum Press wearing an Angora sweater and women’s pants and high heels. Certain of the later films, like Take It Out in Trade, Nympho Cycler, he’s in drag and he seems much more comfortable with it. It’s an open question about where he would be at today.

RES: There are so many contradictory impulses at play in Glen or Glenda, very liberating scenes followed by retrograde moments. I don’t know if he’s sneaking in these liberating themes into a traditional “scientific” framework that was required for it to get made, or it represents an actual split he had in his own thinking. Do you think one or the other is more accurate?

WS: It’s a little bit of both, and we don’t have Ed Wood here to explain his intentions. So the film remains very mysterious because of that. I think Glen or Glenda is a very human film. That’s what I like about it. I think in its confusion it’s very human and so I find it more moving than a lot of better behaved movies about that subject matter.

RES: Just the vision of Bela Lugosi at that age is very moving in itself. What did you take away from their relationship? There is some element of exploitation, I guess, but Ed Wood clearly still cared for him.

WS: I really don’t think it was an exploitative relationship, frankly. There was a transactional dimension to it. On Ed Wood’s side of the equation, here was a star name that he could use to get projects financed. And on Lugosi’s side of the equation, this was work, and he needed work. I don’t think there were any other filmmakers who were giving Lugosi as good a role as Bride of the Monster (1955) in his later years. It’s a movie that treats him as a star. It’s a movie that takes him seriously and it gives him a couple of really great scenes where he gets to act. The idea that he was exploited, I don’t buy it.

RES: I don’t know how true this is, but wasn’t there some question that Ed Wood helped Bela Lugosi get painkillers?

WS: Yeah I’ve heard that rumor. I read an article by Robert Kramer, one of Lugosi’s biographers, who said that Bela Lugosi Jr. resented Ed Wood because he thought that Wood was an enabler of his father’s addiction. I guess the shoe fits, frankly. Obviously, it’s complicated. Edward himself was also deeply addicted to alcohol. So I have a lot of empathy for both men and their struggles.

RES: I’m sure you’ve been asked this a lot, but is there a lesser-known Ed Wood film that you would single out for people to see?

WS: Well, one of the things that I want to do with this book is liberate Ed Wood from his reputation as the worst director of all time and reframe him as a strange director. There are a lot of things that he did that don’t deliver on that same laugh-a-minute level that Plan 9 from Outer Space does. And so if you go in with that expectation, you might be bored or disappointed. But there are some movies like Night of the Ghouls, which is this Val Lewton-ish horror film that he pasted together out of a lot of different incomplete projects and made on a budget that was low even by his standards. It is the most dream-like film I’ve ever seen that’s not directed by David Lynch. The movie that most accurately evokes what a dream feels like…entirely accidentally, I’m sure. Go into this movie expecting a strange experience. You might laugh, but more than anything, it’s a really weird place to be.

RES: The whole idea of the “so bad it’s good” movie has gone through many generations now. But I’m baffled by a new New York Times series on what they are calling “good-bad” movies. They did Road House and Face/Off, which don’t fit the concept for me - these are well executed films. I forced you to read these - what did you think of them and what it says about the whole idea of so-called “bad” movies today?

WS: I read the Face/Off article…can I just quote from the mandate of this column for a minute? It says, “What’s a good-bad movie? It’s the kind of flick that might have you cackling, hollering or groaning. One that is not necessarily great cinema, but is great fun”. I guess this is in the lineage of Pauline Kael’s famous dictum, “Movies are so rarely great art, that if we cannot appreciate great trash, we have very little reason to be interested in them”. And I’ve always hated that aphorism from Kael because she said it at a time when American popular cinema wasn’t being taken seriously as art. So here she came along to basically give her readers permission to keep not taking movies seriously. And I object to the framing of Face/Off as a bad movie as you do, or at least this kind of framing. The whole good, bad movie framing, I think, is very condescending.

I’m reading this article and I’m thinking, OK, you like this movie. You think it’s fun. But because certain elements of it don’t conform to certain standards of good taste you’re classifying it as bad And there’s not a lot of empathy, there’s not a lot of curiosity about why did John Woo make these stylistic decisions? Certainly, I think Face/Off is an internally coherent film. Stylistically it is all of a piece. If you take John Woo seriously as an artist, you can see how it fits in with his larger project. But there’s none of that curiosity and empathy for the work. And there’s this kind of smug sense of superiority that, well, I obviously know better than John Woo. So I’m not surprised to see this in the Lying New York War Crimes. The job of The Times is to be the enforcer of bourgeois taste and opinion. But I guess I am surprised to see a take like this so late. I thought we were past this.

RES: The first article was about Road House and in the original Roger Ebert review he wrote that the “movie exists right on the edge between the good bad movie and the nearly bad”. That’s the jumping off point.

WS: The byline of the author says, “Maya Salam believes the line between good entertainment and bad entertainment can be surprisingly flexible and has enthusiastically debated this logic for years”. I read that and I first think, oh, you think you’re the first person to ever think about this? Like you’re planting your flag on the moon. But secondly, okay, you think the line between good and bad is flexible, but you’re still going back to good and bad as these poles. You’re still making Face/Off conform to certain standards of good and bad. If it’s so flexible, liberate yourself from these categories a little bit instead?

It’s funny that Roger Ebert inspired this because, I highly recommend if you haven’t read it, checking out his review of Shaolin Soccer, because he spends half the review justifying why he gave the movie three stars and explaining the relativity of the star rating system and what constitutes a four-star movie, what constitutes a three-star movie. And he seems to think that this is quite iconoclastic. And he says words to the effect of, listen, if you’re asking me if Shaolin Soccer is a good movie, you’re not asking me if it’s good in relation to Mystic River or American Beauty. Those are two movies that he uses as examples of a four star movie. I happen to think Shaolin Soccer is a better movie. So it’s like reading the diary of a madman.

RES: Are there current bad filmmakers that you are intrigued by or still follow?

WS: We’re fortunate that Ed Wood didn’t become Tommy Wiseau (The Room) right after Glen or Glenda. Tommy Wiseau’s reputation has completely stifled him as an artist. He’s not really been able to produce much of anything since then. And what he has produced has been paralyzed by this reputation. Same with James Nguyen, the director of Birdemic (2010). The best bad filmmakers are probably working in complete obscurity somewhere. A guy who I weirdly admire is Neil Breen. What I admire about him is how he has resisted becoming a Tommy Wiseau-like figure. I remember last year my friend Peter Kuplowsky, who’s a film programmer, he brought Neil Breen’s latest film to Toronto (Cade: The Tortured Crossing, 2023). He had a one-off screening of it. And in his introduction, he said he asked Neil Breen to come, but Breen said, “No. I did an interview once. It didn’t go that well. I’d rather just put it out and not see the reaction. I’d rather just keep working”. And I admire that about him. Nose to the grindstone. Don’t become a traveling clown. Don’t become a dunk tank guy. Just do your work.